The Blind Canadian is the flagship publication of the Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB). It covers the events and activities of the CFB, addresses the issues we face as blind people, and highlights our members. The Blind Canadian:

• Offers a positive perspective and philosophy on blindness

• Serves as a vehicle for advocacy and protection of human rights

• Addresses social concerns affecting the blind

• Discusses issues related to employment, education, legislation and rehabilitation

• Provides news about products and technology used by the blind

• Tells the stories of blind people

• Covers convention reports, speeches, experiences

• Archives historical documents

EDITOR: Doris Belusic

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Kerry Kijewski

PREPRESS, PROOFREADING & WEB DESIGN: Sam Margolis

The Blind Canadian, published by the Canadian Federation of the Blind, comes out twice annually in print and on www.cfb.ca in web and pdf versions

The Blind Canadian welcomes articles, resources and letters to the editor for possible publication.

We thank Victoria Foundation and the Federal Government for a generous grant which helps fund this educational outreach magazine.

Canadian Federation of the Blind

Douglas Lawlor, President

PO Box 8007

Victoria, BC, V8W 3R7

Phone: (250) 598-7154 Toll Free: 1-800-619-8789

Email: editor@cfb.ca or info@cfb.ca

Website: www.cfb.ca

Find us on Facebook

Twitter: @cfbdotca

YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/CFBdotCA

Feature Article: Donna Hudon: Advocate, Pioneer, Personal Support Worker

Editor’s note: A long and winding road which Donna paved with hard work, self-advocacy and belief, determination, perseverance and positivity, ultimately led to her success as a personal support worker in her community. Federation leader, Mary Ellen Gabias, said she doesn’t know of another blind person in North America doing this type of work. Donna is truly a role model we can look up to and learn from.

Below is a transcript of an interview with Donna on Outlook On Radio Western, aired lately through the University of Western Ontario, with blind sibling hosts, Brian and Kerry Kijewski. Also found on podcast. Thank you to Brian and Kerry for permission to print this important piece. ~ Inspired by CFB ~

Kerry: Thank you for tuning into Outlook this morning. I am here with my brother on 94.9 Radio Western. Today we’re speaking with Donna Hudon about her blindness and some of the other barriers she’s come up against and the job role she’s in right now.

Brian: Yes, I think a real focus is going to be employment because we talk a lot on this show about the high unemployment rate in the blindness community. Obviously, that’s true in a lot of cases unfortunately, but yet it’s also really important to show some success stories on this show and this is definitely a great example of one.

So, welcome to Outlook, Donna. Thanks for joining us today.

Donna: Good morning.

B: So, for our listeners, whereabouts are you calling in from today?

D: I am calling in from Nanaimo, B.C. I’m on the west coast of Canada here on Vancouver Island. I’m just coming off of working a 12-hour shift. So I worked from seven at night till seven this morning and it’s eight o’clock in the morning now. Generally, I’m often awake, off and on, at night time anyhow, so working nights works for me. I read books, exercise on downtime, and do all of my household chores and caring for the young boy that I care for.

K: Well yeah, actually our mother does this sort of work and she’s done night shifts in the past, but she’s getting older and it is taxing for some people. And like you said, other people seem to thrive at that time of night.

I just thought I’d quickly ask, since you mentioned it, do you have any idea if your issues with sleep have to do with circadian rhythm? A lot of blind people have trouble knowing their body, telling them the time of day. Is it like that or not?

D: I think so. I genuinely think so. Some people might diagnose it as non-24 because it’s more than just a sleep pattern. It’s also your eating pattern. It’s all your circadian rhythm.

B: I’d heard a bit about the non-24. The last I’d heard, it was only officially diagnosed in the US. I don’t know how it’s recognized yet here in Canada. I’ve learned a little bit about it because I do find it to be an interesting topic as well.

K: Does that mean you’ve been blind since birth? Do you have any sight currently?

D: No, I’ve actually been totally blind since I was 23. I’m 54 now, and I went blind from retinitis pigmentosa. So, I lost my sight quite early at night time. I could see in the daytime and had fairly thick glasses when I was, maybe, around six years old.

By the time I was 10, 11, 12, I had to use a cane at night, because my eyes didn’t adjust to night vision. And then I had tunnel vision that was slowly closing in. By the time I was 23, I was totally blind.

K: Yeah, we speak with several people with RP on this show. It affects people differently, of course, at different stages, but normally it does start to show up in childhood at night and then it progresses from there often.

So, what was your childhood like then – did you guys know what was happening? Was it hard to get diagnosed? Or easy? What was that like at the beginning?

D: For me, I think I had an early diagnosis. So, I think my eyes were quite, you know – when you look in somebody’s eyes that has RP, you can actually see it. That was one of the characteristics. Whenever I went to an eye doctor, they’d have a resident there and they’d say, “Do you mind if I ask something – to see your eyes?” You could actually visually see something going on in my eyes. So I knew, as a young child. We didn’t have training, as you know, in Canada.

I grew up in Edmonton and I just had a mom that recognized that, “Okay, you’re going to be blind. You’re gonna have to just do all the work, as if you can’t see now.”

Doing dishes, she taught me to use my hands and to feel everything. Vacuuming, it was, “Vacuum end to end.”

Same with washing walls, windows. I was expected to do the same work my sisters were doing, I just had to learn how to do it more so, like, I couldn’t spot clean.

K: Yeah, you might miss things, but there’s so many ways to do things, like dishes, without sight. Often I find that sighted people miss something. I feel the dish later and like, “Oh, that’s kind of crusted on there, and they were just looking often and I caught it.”

D: Exactly. Yeah, if you rely on your eyes only, you’re gonna miss a lot. If you rely on your hands and the way things feel, you tend to get a lot more information.

And then also, because my mom knew I was gonna go blind, she seemed fit to see me travel the world. So I got to go to a lot of different countries as a young child.

B: Oh, wow., that’s also so important. We talk a lot about travel on this show. And actually, John Rae, we had on the show just over a year ago. Unfortunately, he passed away, rest in peace, but he talked a lot about travel and how important travel is – even more so for somebody who can’t see – because it really does change your perspective. You take so much in just from being in a different environment, a different place. And part of being blind, a lot of it is adapting and being constantly able to adapt quickly in a situation. And when you’re in a new place that you’re not as familiar with, that gives you the chance to really just use those skills on the spot and try to navigate in the moment. And, I think that is such an important part.

Give us a few examples, what kind of places did you visit growing up?

D: Um, well, England, Malta, Singapore. My dad had a home on stilts in Borneo. Um, Japan. Yeah, I got to see a lot of things – ride on an elephant, swinging in a jungle, walking along beaches in the ocean, seeing actually what a red tide looked like; a lot of memories, a lot of visual memories I have.

K: Yeah, and that’s a common thing, where they’ll write articles about people who are going blind who want to see as much of the world as they can before they go blind. So that’s a very common feeling that people have. Even myself, the things I got to see while I could, I do cherish that, even though there’s lots of ways to be and you adapt for sure. But it sounds like, kind of like us, you had a great family and a great mother.

B: Yeah. We talk about the support system being so important and based on what you said about growing up there, it sounds like you did have a really great support system. And also, it’s the idea of being diagnosed with RP – obviously it’s not an easy thing for anyone to deal with at first – but accepting it instead of constantly trying to fight that. It sounds like your mom really stepped in and started to adapt to that, instead of just saying, “Oh, what can we do to continue to try and save your sight that you have left?”

D: My mom started trying to baby me and then my older sisters recognized that I went from this sweet, young child to being this rotten little brat, and they said, “Mom, no.”

K: Yeah, that’s something sisters can point out.

B: Yeah, that’s interesting. I like that.

D: You know, “Look what you’re doing to her. No, Donna, you have to do all the work that we do. You don’t just get to sit on the couch.”

K: And there’s talk about how to do it with blind children, where, if you just give them everything forever, then they’re never going to reach out and get things for themselves.

D: Yeah. Now thinking about all those skills, that’s probably how I got the job that I’m doing now.

K: Right, and those skills build over time often, just like anybody.

D: So, no formal training, you just gotta do it.

K: I was gonna ask, growing up, did you get any assistance in school, for travel, or any other skills you needed?

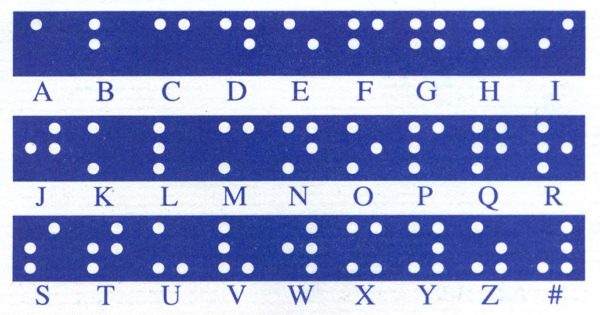

D: Yeah, in school I did get a lot of mobility training. Unfortunately, the other type of assistance – because I am from the age where they didn’t really want to teach you braille – they wanted to teach you how to use your weakest sense the most.

So, there came a time when the blue lines on paper and the print on paper was too light for my eyes to pick up. So, they gave me an overlay of a yellow page to make that print darker instead of, “Okay, let’s teach her braille.” They started making print bigger. So it’s not skills that I can use now, but the mobility, definitely I had fantastic mobility skills, yeah.

B: I think it’s interesting that you point that out, because that ties back to what I said earlier, about acceptance and dealing with this, and braille does still seem to be one of those areas in a lot of places – whether it be a school board or whoever is charge – they often don’t see that as a necessary thing. Or, they try to hold off as long as they can.

K: It’s like, it’s intimidating to them, “Oh, that would be really hard to learn that for someone or to teach that, so let’s avoid it as long as we can.”

B: And like you pointed out, keep focusing on the weakest sense, your vision. “Oh, how can we make this larger?” and all this, which sure, okay, to a point, but really you wanna be doing maybe both, a little bit of that, but you also really want to be spending your time to learn braille. It’s unfortunate, but hopefully that changes. But you hear mixed feelings and thoughts on that, how that’s going these days.

D: I got basic braille. I got letters, “This is what a letter looks like.” But there wasn’t an expectation, “Donna, you’re not gonna be able to read. You should learn how to use braille.”

K: But, as far as guide dogs, I know you’ve had guide dogs in your life as well. You’ve used a cane, but do you prefer guide dogs, or can you go either way?

D: I go either way. You know, it really depends on where I’m going, what my atmosphere is like. If I’m going out for the evening, I’ll use a cane. If I’m going out to walk, most places I’ll use my dog. But I’d rather keep my cane with me, so I do have a folding NFB cane because they will fold and I’ll pop it in my purse, just in case.

K: A backup.

D: Yeah. But I’m quite comfortable with my cane.

K: Okay, yeah, because some people really take to guide dogs and then the minute that they can’t use one for some reason, it’s really hard to go back and forth. And other people are pretty good either way.

D: Yeah. I started using a cane when I was ten years old.

K: That’s good. Take away some of the shame around the tool that it is.

B: Yeah, because I remember when I got my guide dog, I don’t ever remember specifically carrying a cane as a backup. I mean, I was just in high school and wasn’t going out a lot at night. But now, getting a bit older and thinking about it, it does make so much sense that in a certain situation you might still want to use your cane to find something.

It’s also important to mention that I think it’s great perspective to see that you use both when it’s applicable, because I still get the question quite a bit when I just have a cane – I don’t have a guide dog anymore – people will often say, “Haven’t you ever considered getting a guide dog? How come you don’t have a dog?” And it goes back again to everyone’s situation is different, everyone has different preferences, and it doesn’t mean that a guide dog just solves everything for anyone, obviously. It’s just one tool amongst so many things that we need to navigate.

K: No. But they’re lovely companions to have when you have them.

D: It’s like driving a car, right? Sometimes I just want to drive in the car, but sometimes I want to find the bus stop. My dog isn’t always the greatest when relying on him to find something.

B: So, we haven’t gotten into your work yet, but we’ll get more in depth into your work as a personal support worker. I know you work full time for the Nanaimo Association for Community Living. You also work somewhere else part time.

D: I was always interested in working with people with other disabilities and that’s what I do. I work with people with disabilities.

When I was growing up, like 15, 16, 17, I started volunteering in Edmonton. If a festival was coming and they had a disability group to look at some of the logistics of people with disabilities attending, I would volunteer to be on those committees. And then, I actually took my Rehabilitation Practitioner diploma in Edmonton. I was 19, I think, when I started. And that’s leading to the job that I do now.

K: That’s the thing. Some of these skills we pick up over time. And I know you moved to B.C. there in that time too, and that you have two children. How old are they?

D: My daughter will be 22 and my son is 24.

B: And, maybe, just a quick touch on that because we’ve talked to a few parents on this show that happen to be blind and that whole experience. Did you get some pushback at the time from anyone? What were some of the difficulties that you faced, either yourself, or more so from society? Or, some of the positives that came from that as well?

D: Hmm. Well, I also homeschooled my kids. I went to all the baby groups and I got all the supports that I could. I live in a fabulous community and am well supported in my community.

K: So, most people didn’t have reactions that you can’t do this? Or, maybe that didn’t happen to you? We aren’t parents ourselves here, so it’s good to hear from blind parents, because it’s a voice we haven’t heard enough from.

D: There’s definitely people – I remember one time, standing with my sister-in-law and her saying something like, “How are you gonna stop Daniel from eating dirt?”

And I said, “Well, you know, both of our kids probably have got dirt in their mouths right now.” You know, like, parents don’t stop their kids from doing those sorts of things.

B: Yeah, I’ve definitely had sand in my mouth a few times as a kid, I’m sure. My parents can see, so it doesn’t make a difference.

D: Yeah, but being blind, I can also pay attention a bit more to what’s happening in the next room. I’m a little bit more aware of things because, like we’d said before, when you’re just relying on your eyes, you’re gonna miss a lot.

K: Yes. Thank you for sharing that message on our show, because I think it’s a really cool one and very true.

B: Yeah. We understand that if you’ve got eyes, you’re gonna use them and it’s one sense. But yet, it is always looked at as the eyes still being the dominant sense or the one that people more so focus in on, when really we do have these other senses that can tell us so much, if we open up our minds and let them.

D: And, just open up to all of it as an experience. Don’t limit yourselves to just what you can see.

B: And it’s always great to talk to a blind parent on this show, because I do think that that misconception is still out there. A lot of it is that most people just don’t know anyone who’s blind either, but a lot of people would still probably assume, “Oh, if you’re blind, you wouldn’t be able to be a parent.” So, it’s just so good to make so many more connections in the blindness community and really start changing these misconceptions.

You wanna talk a bit about after school and going off to college or university and that experience.

D: Alright. So, I’d just graduated high school and wasn’t 100 percent sure what I wanted to do, wasn’t able to get a job because, at that point, I was now – I had been legally blind since I was six or seven years old, in the legal terms of blindness. But by the time I was 18, 19, now I’m getting significantly blind. I’m not seeing in dim light. I’m using a cane all the time. I can still see in front of me, to read. Computers have just started. I didn’t take on computers because, at my age, I thought, “Oh, computers, it’s hogwash. I’m never going to use a computer.”

B: Yeah. It’s a fad, right?

D: So, I didn’t take the Wayne Gretzky computer camp that they offered, but here I am – I was on assistance. I went in there and they were talking to me about, maybe, me being unemployable. And I said, “Oh, I don’t know, I think I can still get a job” and I said, “Why don’t you give me a job?”

So for six months I was a secretary for the ministry, because I could still see to read, so I could file, and I learned how to start using a computer, because it was just basically a black and white screen, clicking on the person’s name, answering the phone, that sort of thing. I realized I wasn’t going to be able to do that for very much longer and applied to get into the rehab practitioner program in Edmonton.

K: So, what was that course like?

D: I loved it. Do you know who Diane Bergeron is? Is that her last name?

K: Yes.

B: Definitely know the name.

D: Well, she was in my class.

K: I think she’s big there at the CNIB.

D: So me and her actually started college at the same time. And there was another gentleman there who was also at a different level of being able to see.

So, through school I felt supported and it was like this: the first year of college, I could see to read. Then, over the summer I didn’t read, because I was too busy having different kinds of fun and not reading. And I went back to school and looked at my books and went, “Oops, I can’t read anymore.” So I bought my first DOS-based computer and learned within two weeks on how to use a computer.

And because Diane was already in my classes, they already were giving all of our schoolwork in alternate formats.

B: Right, and that’s an interesting thing that you did, have somebody else who was blind or low vision in your course there, so that you had that. Because a lot of times we are, as blind people, we’re often used to being pioneers or whatever you want to call it.

K: The only one in the room.

B: We’re the first one starting something out. I took Music Industry Arts here at Fanshawe College and there had been some people in the past, but I think there was nobody in the year that I was in the course. I was the only blind person. It did go pretty well, but overall it wasn’t quite the same. They didn’t have experience from already having somebody blind there at the same time.

D: So, what’s interesting though, is that we were going to school for rehabilitation practitioner, which is working with people with disabilities, both physical and mental disabilities, as well as mental illness. It was one thing that we touched on. Little did they tell us, or me, that when I graduated from school, that nobody would hire me to do this job.

I’m now blind and nobody wants to hire somebody who’s blind to look after their disabled, non verbal, full-care, part care – don’t think I can look after my own needs, let alone look after other people’s needs.

B: Yeah, well, I mean, the school experience for anyone, even a lot of people in general, you go to school and hope you’ll find something after, and it can be a challenge for anyone. But yeah, especially in our society where people still aren’t open minded and aren’t aware of the capabilities of blind people. They often look at that as being something that is a negative or that prevents someone from doing something.

D: You know, I was well supported. The only way I wasn’t supported is I didn’t – I went into school being a non-blind person. I took on very limited resources and assistance, for some reason, maybe pride goeth before me, or something like that. It wasn’t until my second year of college/university that I realized, “Okay, well, I need those resources. Now I don’t have a choice.”

Had I done it over again, I would have definitely taken those resources right off the bat. I don’t see that there’s a shame in being blind. I just didn’t really know that you can get assistance.

K: Yeah, just knowing to ask for something and not feel like you’re imposing or something.

D: Exactly. Like, am I asking too much? Because I can still see, but not really.

B: That is a big difference. I mean, for me, I’ve been born blind and I’ve always had just a little bit of light perception but my vision’s never changed, so when I go into school, that’s the way it is from the beginning, the whole time through. Whereas, if you’re losing vision throughout that time, it does make it different. But it’s also the whole fact again that, even for me, being blind my entire life, there were certain services at school that I didn’t jump on right away. Like, I could have got a nicer laptop covered for the work that I do, but I had one at home that was older that still worked and I just didn’t. You know, you’re already so busy with schoolwork and occupied, that to look into this accessibility stuff is another thing. So I just stuck with the one I had and after I kind of regretted it. But it’s something we all sort of deal with. It’s like, how much should we ask for help versus doing things on our own? And it’s always a balance, like most things.

D: And maybe their jobs aren’t to go to you and say, “Look Brian, you can get a really nice new computer. I know you have this one, but that one you’re using is three years old. We can give you a brand new one, jacked up.”

B: Right. I’m not a five-year-old where they’re trying to tell me what they can offer. As you become an adult, that’s something we talk a lot about, it’s speaking up for yourself, having the confidence, and asking for what you need. You do have to step it up a bit. Not everyone’s gonna be knocking on your door every morning saying, “Get up, time for school.”

K: But I do like how you, Donna, just asked that one person, “Well, you could give me a job” and you became the secretary for a couple years. That’s amazing speaking up that not everybody, unfortunately, feels comfortable doing.

B: Absolutely.

K: Tell us a little bit about what led you here. You had two children you were raising and now they’re grown and we’re gonna talk a little about your job. So, what sorts of things led you to this position of personal support worker?

D: Going back before my children. I moved to Nanaimo. I was dating someone and he had moved to Nanaimo prior to me. So, I moved to Nanaimo thinking, “Alight, I’ve got this diploma that took two years. They weren’t even offering it in B.C. They were just bringing on a six-month program in British Columbia, so I applied. I got up and applied for work as if I had a job, 9 to 5, and nobody would hire me, including where I work now.

Now, we have to recognize that I do a job that: a) a lot of people don’t want to do, and b) I don’t know anybody else that’s blind that does it.

B: Yeah, and we’ve got the same sort of question. I’ve never – not that I’ve done tons of research on it – but like you say, I don’t think I know of anybody, and the fact that you are in that area of work and you don’t know of anyone, that’s a sign that there aren’t very many. That’s for sure.

D: No. I do know one gentleman – I just met him and he works for the same company, and he can see on his sides, not straight ahead. I don’t know what he’s got.

K: Peripheral.

D: Yeah: He’s got peripheral vision, but I don’t even know if he recognizes himself as blind or not. I’m not sure.

K: That’s that line we were talking about before, about being legally blind. Don’t you just love that term?

B: That’s such a funny term.

K: It’s a spectrum.

D: Yeah, but honestly, not a whole lot of people do this job. So I got a lot of doors shut on me and so I decided to go back to school because I wanted to focus on working with youth and children. So, I went back to school and got my degree in child and youth care, where I specialized in child protection, which is another job where people don’t recognize that you, being blind, could go into a situation where possibly you need to be doing child protection. So, I had a diploma where nobody would hire me and I had a degree where nobody would hire me.

B: Well, that’s such an important thing to point out, because so often in the world we’re focused on the education system, which of course is important, the education is needed especially for certain types of jobs, but yet, there’s so much focus on that education part, that – you go through all that and that’s fine – but then after that is when the real difficulties do begin. And it’s unfortunate. You probably feel like, at that time it’s like, “Oh, if I’m educated, there’s no reason I shouldn’t be getting a job here.” It’s gotta be frustrating.

D: Yeah. Even getting my practicums, with doing the child protection, you had to get a practicum with the ministry, and the coordinator had said, “Do you mind if I ask the other social workers what they think about a person who’s blind doing a practicum here?” And I said, “Okay, well, if you’re gonna do that, will you do me one better and will you tell them that Donna Hudon is looking to do a practicum?” Because sometimes people can say no to being blind, but I am an active community member. I volunteer. I belong to boards. I went to school with a lot of the people who are the social workers. They know me. I don’t want it to just be based on my disability.

K: Well, this blind person wants the job and now it’s like, they’re deciding by committee if this bunch of people think they know about blindness could say whether a blind person could do this.

B: And that’s also taking out the individual of the situation where, of course, it’s not every blind person is gonna be fit for this job, because not every blind person has these social skills, has the experience. Like, again, that’s such a generalization, when really it should be, “What can this person do?” And that really demonstrates again about looking past the blindness as just one part.

D: But, I didn’t wanna face yet another discrimination, being blind. You know, I can’t even do my practicum? I paid the money, I did all the extra classes, and now you’re telling me that I may not even be able to do a practicum?

K: Yeah, so close. That’s frustrating. And, like you said, you’re tired. You worked so hard and then you come up against this wall that somebody has decided to put up.

D: Because they don’t know. Because it’s fear. It’s all fear based, right? F-E-A-R: fictional evidence appearing real.

You know, it’s easier to say “no” than “yes” because saying no means no responsibility for saying yes. “Let’s work on it” is more challenging than just saying, “No, it’s not going to work.”

B: It’s such a good point, that the fact that there really isn’t evidence you can use because, like we just said, there’s not that many blind people doing these jobs. But, yet to get the evidence, you have to give people the experience that they are qualified for in these positions, instead of just, out of fear, turning them away from the beginning.

So how did that go? You did do your practicum at some point then?

D: I did. And I now work for a very wonderful company. I’ve been working there for five-and-a-half years now.

K: Right. We heard you speak at a conference [CFB convention] before the pandemic, about some of the systemic barriers you were coming up against and the human-made barriers, resistance for the job. And then when you got it, some of the duties you were restricted to do. So, you really spoke well about it that day.

B: Yeah, If you wanna talk a little bit about getting that job as the personal support worker for the Nanaimo Association for Community Living and then how that whole experience went getting the job. And then after you get the job, like so many things in life, you get something and then it’s like, “Oh, great, we’re all set now,” but then there’s a whole other set of things to deal with.

D: There is. So, I wanna premise this by saying, I work for a fabulous company who really are inclusive and they have now, at this point, been working on a policy for their procedure manual – how to have somebody with a disability work to being an independent worker.

K: Right, and that’s great to point out where we are now and the positive things that have come from it, before we talk about some of the barriers, because it’s not all gloom and doom.

B: Yeah, we don’t wanna sit here focusing on all the negatives, especially when it did work out and you work for such a great place that is very inclusive, once you worked with them and they learned a bit about what people could do. And again, that’s why we talk and it’s so important to start hiring more people with blindness or any disabilities or any nationality or all these different diversities and intersectionalities because, ultimately in the end, it just provides for so much more information and enrichment and, for the future, for more people to be hired into a company that would, in the past, just be refused due to fear or just lack of knowledge.

D: Exactly, yeah. So, when I first started applying there, they were more than willing to give me an interview. I interviewed very well. Gave them my references. My references were very impressive. Again, I volunteer – and I suggest for people to volunteer in their community. If you’re not working, be active, push yourself. So, that’s what I did. That’s what I was brought up with, push yourself.

So, I had the references, and then they said, “We need to research the possible risks for somebody who’s blind, working with the population that we serve.”

K: Yeah, what did that mean?

B: Yeah, where would you get that research?

D: Yeah, they’re not gonna have that research. They’re not gonna have that research, because there’s not enough people. Honestly, when you even Google it, it will show the blind person being the disabled person, it doesn’t have the blind person being the care worker. So there’s not really any hints and tips on how to do things because, putting it all together, it isn’t available because there’s not enough people who are blind doing it, therefore there’s not enough research.

I’m very tenacious and I’m one to push, and so they gave me a job.

K: Well, earlier you were using a specific example of one of the tasks that you sometimes have to do while taking care of people and how you just spoke up about it.

D: So, one of the tasks, after I did get the job, when I sat down with my program manager. We were sitting in the house and she was asking me how am I gonna vacuum and cook a meal and do certain tasks that would be expected, laundry, things during the day. And then I said, “You know, I thought you were gonna ask me how I was gonna wipe somebody’s bum” because I’m doing full care, you know, that’s one of the tasks.

And she says, “Well, now that you’ve mention it, how?”

And I had told her, “Same way I wipe my own.” And, I do kind of feel sorry for the sighted population and what they do when they have to go to the bathroom and it’s dark out or you’re outside in the woods.

K: I guess they bring a flashlight. If they don’t have one, I don’t know.

B: Maybe as humans, we figure things out when we’re in a situation and we adapt.

D: I guess, but myself, I know how to wipe somebody, wipe myself.

B: You’ve had a lot of experience. You’ve also had two kids.

K: But, the other piece of it, once you figure out how you do these tasks and some of them you already do anyway, but it’s the thing about how you’ve always wanted to work with children with disabilities. And, the fact that you have a disability yourself, it gives you an in with them that someone who might not have a disability wouldn’t have. So that’s where you can bring so much value to the people you look after, but I’m sure there were a lot of technical things you also had to do.

D: The connections, the hope. I’ve worked with people at a day program who say, “Wow, you’re working for NACL? Maybe I can get a job, too.”

B: Right. And that’s what it’s all about. It’s seeing more of us, people who happen to be blind in these areas, and then somebody else who has any disability will see that and say, “Oh, before I’ve never seen this and now I have, so maybe it is possible.” It’s like anything, having a role model or people to look up to.

D: One of our human needs is contribution. And so I think that, not only am I contributing to where I work, but people can see that they can have that contribution as well.

K: But some of the technical things, one example I can think of is, what happened with medication giving, because I know that’s an important part often?

D: Alright. So, with NACL, I have my medications, the PRN’s, the ones that are emergency meds, I have those in a bubble pack where I have “Way Around,” those little tags, stickers; but with NFRP (Nanaimo Family Resource Programs) where I work, the kids have G-tubes, so we are pulling meds with syringes. I use AIRA.

B: Right, and for our listeners, maybe just mention briefly what that is. But, was that a bit of a struggle to get permission to be able to do that, originally, because that does involve somebody else, bringing in a third person over your phone to read something for you?

D: So, with NACL, it still is a bit of a struggle. But with NFRP, they adopted it, went through the ministry, as it’s working with children.

Because AIRA is, they’re vetted. I can give them my credit card number and it’s their job.

B: Right. It’s a paid position they have. There’s some security going on there.

D: There’s security and privacy and what not.

K: Because blind people need to ask the AIRA agents so many things, so many personal things, like when they need a card read or something, so you can’t have so many limits all of a sudden or then it’s not useful.

D: Yeah. So I’ll use my tags when I pull the medications with the list on my computer. I’ve taken the picture from the MAR (Medication Administration Record), I pull out all my meds, pull out all my syringes, lay them in front of the meds, and then I phone AIRA and I say, “K, can you check the date on the medication, the name, making sure that it’s the right child’s name.” Things, just to make sure of the medication and the dosage.

Then, I have the syringe in and I tell them, “Okay, so then just tell me when to stop at 5 mls,” because at that job, one person is drawing meds, the next person – there’s two people working – one person draws them, one person checks them right away before they give them to the child.

B: Right. You have that double check there to make sure because, obviously, this is important stuff and you don’t want to be mixing anything up, so it makes sense that they would have that system in place.

D: Right, so with the use of AIRA, it is having somebody’s eyes on it. It’s not just depending on a tag. It’s actually having somebody’s eyes on that bottle.

B: Wow. So, I mentioned the Nanaimo Association for Community Living, but you also mentioned the other acronym and I don’t know if we described that on air. So, that’s your part-time job alongside?

D: Right. A casual one. I’m one of these people, I’m a home owner in Nanaimo and with the rising cost of housing, with everything, groceries and taxes, I’m one of those people who need to have a full-time job, rent a couple of rooms, and have a part-time job as well. They took off running and accepted me being blind there, because I had already shown myself with NACL.

And NACL, they went from not wanting me to work independently with somebody with a disability, not wanting me to give meds.

As open as they were able to, still with restrictions. And every year, I would go to them and say, “Okay, well, let’s lift the restrictions. Well, okay, I’m ready to push those restrictions” and that’s unfortunately sometimes what people who are blind have to do, not be is complacent, and just to realize, if you think you can do a job, then do it. Show them that you can do it, because now, I’m a night shift worker. I work independently with one single client, with a child.

B: Right, whereas originally, they weren’t as open to letting you do a night shift when you were by yourself.

D: Couldn’t be by myself. Couldn’t have other staff leave the house to deliver the garbage somewhere else and me be by myself in the house for any length of time. Couldn’t start my shift a half hour early and I would be the only person there.

K: Yeah, it really does separate you out from everyone else.

D: It sure did.

B: Again, I think you make such an important point. You get the job, that’s amazing, that’s a great start. But then from there it comes back to, sometimes we talk about on this show about not just settling for something. Of course, when you start you might not get every opportunity that everyone else does, but over time you start to realize that and you start to fight to get the same rights that everyone else has. Instead of just being like, “Well, at least I got this job and they’re letting me do most things, so that’s enough.” I can just tell by your personality, you’re not just gonna stand for that for long and you will speak up about it and that’s how change happens.

D: And now, they’re putting into their policy and procedure manual, how to hire somebody with a disability and to have independent work. So, going from: they wouldn’t hire me, to okay we’ll hire you with restrictions, to now we’re inclusive. Now, if anybody else is blind hearing this and wants to do personal care, come to Nanaimo, it’s a beautiful city.

B: There you go.

K: And again, today, we’re talking about this position, personal support worker, because it is one of the more difficult jobs somebody might think for someone to do. But here we have an example of somebody doing it, and we don’t want that to be the last or the only one.

D: No, no, like I said, anyone else wanna come and do it, come to Nanaimo. I’ve got a spare bedroom to rent you.

B: There you go. You might get some sort of deal for accommodation compared to some of the places out there. It’s not easy out there, that’s for sure.

D: Sometimes it’s really not easy and it’s certainly not well known that 90 percent or however many percentage of people who are blind are living in poverty, not because they’re not educated, not because they can’t do the job, but because somebody’s just not giving them a chance. It’s easier to say “no.”

K: Right. And as you say, your company has changed that and you said somebody within the company there has been taking disability studies courses and really learning about it.

D: They have been. They are really learning and understanding. It is quite fabulous.

K: And if the patients or the clients themselves, the children, if they themselves have disabilities, anybody working with them, doesn’t it make sense that the more they study about disability, culture and all these things and how it works, that’s only gonna benefit everybody.

D: I worked with some lovely adults. I work with children now, but I’ve worked with adults for the past years and people within NACL who just need multiple supports. And it is nice for them to see that somebody who’s blind, some people just need to be able to see that they can help you. And when you need so many people in your life supporting you, and I can give that little hope to somebody, “Hey, can you pass me that glass because I can’t see it. Can you help me, here?” It does, it helps humans to feel good.

B: Well, yeah, it’s the back-and-forth. Of course, everyone, whether you’re blind or you have a disability or not, we all need help from someone, we all need support from people, but yet we also all wanna be able to help other people. And sometimes, when you are blind, you’re looked at as the person that needs the help and won’t give the help. So, to have that responsibility to be able to help others, that must feel so rewarding. It isn’t something that happens enough in the world, and to have more blind people and people with disabilities out there in the workforce, it really is just a wholesome way for everyone to learn and grow and make companies more inclusive and to be able to have the best staff they can because they’re not discriminating against anything. They’re looking at the person and focusing on what the person can do and how important that is.

K: Well, let’s end on something you do on your time off.

B: Yeah, it sounds like you do a lot of work, really hard worker.

K: But, yeah, you were telling us before we went on air about your kayaking and your dragon boats.

D: I do. I have a double kayak, an ocean kayak that I usually have down at the docks on the ocean, so always willing to go out with different people. My daughter is one of my main partners. My sister and I are actually going to the Broken Island Lodge and spend four nights of beautiful kayaking and being spoiled with great meals at the lodge. We’ll do that in July.

I also dragon boat. I’ve been on the same dragon boat team for 19 years and I’m working to be a competitive dragon boater on a competitive team now, because I actually had breast cancer three years ago and now I can be on the Breast Cancer Survivor team.

K: Oh nice, which is great for feeling included and better about things when you have others who understand and then you work together, such an important team project as rowing one of those dragon boats.

D: It really is great, that working together.

B: Yeah. And we talk a lot on this show about sports and activities, and when you’re blind, that’s another area that sometimes gets left out or people think, “Oh, you won’t be able to do this or that, or keep up.”

K: Or, it’s not safe for you to kayak on the ocean or something.

D: Or, in the gym or anything else. It’s really not safe for you out there if you’re blind. Could be a perception, but.

K: Oh, so tiring sometimes, but it’s good to be able to talk about it sometimes, I think. It takes some of the weight and pressure off it all.

B: Well, that’s the other thing. We do so much advocating with this show, we’ve been getting more involved in advocacy the last few years, but it can be exhausting, and somebody like you, I know you’ve been dealing with it your entire life, working in advocacy and even just getting the job and really fighting for all your rights there. That’s advocacy in itself and it really demonstrates that for society.

D: I loved when I connected with the Federation (Canadian Federation of the Blind) because it had the same philosophy that I’ve always carried about blindness that: “It is not the thing that defines you.” I know so many people that are blind with so many different attributes and things that they can do and I just don’t think that you can just say “no” to somebody simply because they are blind.

K: Exactly. That’s what we say on the show, so we appreciate having guests on like you, Donna, who can share that with our listeners, so it’s not just coming from us all the time.

So great. You said it’s this summer is when you’re taking that trip with your kayak and your sister?

D: I am.

K: That sounds amazing and I hope that you have a great time and have some well needed time off by then, which you’ll need I’m sure.

B: Absolutely. This has been such a great discussion, Donna. We really do appreciate you coming on this show and we’d always love to have you on again some day. So, all the best to you.

D: I appreciate that. Thank you.

K: Have a good rest with your trip this summer.

B: Or maybe, it’s time for a rest now after your 12-hour shift, and your debut on Outlook here today.

See you guys next week.

• Podcasts: Outlook On Radio Western wherever you get your podcasts.

• Email: outlookonradiowestern@gmail.com

• Twitter @outlookcfb

• Facebook.com/outlookonradiowestern

Learning About the Halifax Explosion

BOOK REVIEW on The Blind Mechanic

by Thelma Fayle

On a recent June visit to Nova Scotia, we had a chance to visit the stunning LEED-certified library, built to look like a stack of books on the Halifax horizon – a story highlighted on CNN; the moving immigration museum, Pier 21, featuring immigrants who have helped build Canada; the art gallery – full of Maude Lewis’s fabled work; and the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, presenting insights from the Titanic disaster among other fascinating stories. Throughout our two touring days, guides made frequent references to the “Halifax explosion in 1917.”

I wanted to learn more about the tragedy, but did not want to read through a history of the moment the munitions ship, the Mont-Blanc, exploded in the Halifax harbour. At the Maritime Museum, I found a copy of The Blind Mechanic, by Marilyn Davidson Elliott (Nimbus, 2018). Learning about one family’s experience seemed a good way to get a sense of the event that marked the growth of a city in the same way tree rings from a year of drought mark a tree even a hundred years later.

This is from the jacket of the book:

Eric Davidson was a beautiful, fair-haired toddler when the Halifax Explosion struck, killing almost 2,000 people and seriously injuring thousands of others. He lost both eyes—a tragedy that his mother never fully recovered from. He also developed a fascination with cars and how they worked, and he later decided, against all likelihood, to become a mechanic.

Written by his daughter Marilyn, the book gives new insights into the story of the 1917 Halifax explosion.

Marilyn was only able to bring herself to write the book about her father after he died. “I knew that dad was extremely humble, and he would have considered a book about him to be boastful,” she said, explaining her decision to write about him after he died in his 90s.

Following the explosion, once he recovered from his injury, Eric attended the blind baby nursery. That option seemed to help his naturally overly-protective parents. Eric adjusted quickly in those first few years and did not seem to suffer mental trauma; whereas his parents, like many other survivors, referred to as “refugees,” suffered mentally with a form of PTSD, although they didn’t call it that then.

Two years after the explosion, when the little boy developed a fascination with cars, Eric’s father wrote to the relief commission, asking them to help him locate an old junk car for his little boy to play with in their backyard.

Eventually, the school for the blind in Halifax, offered Eric an education comparable to the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston. He learned to read and write Braille, along with other interesting subjects; but the main skill he learned was to be independent. He wanted to learn to play the banjo, but they didn’t teach banjo, they taught piano. So, he learned to play the piano, and then later in life he decided to teach himself to play the banjo.

As an adult, Eric looked back on his childhood as a boy who ran, walked, swam, and skated with kids in his neighborhood. “I never considered myself blind or any different from them; and they never really considered me any different,” he recalled.

He was one of those people who figured out early in life what he wanted to do for a living. He wanted to be a mechanic, but was not sure if he would ever get the chance to fulfil his dream. He decided he would have to teach himself and was able to get his brothers, parents, and sister to read the manuals to him. He experimented on the old Chev in his backyard. He took the engine apart and then put it back together. He taught himself everything he could about auto mechanics and worked on any car he could get his hands on. In 1948, he received his automobile mechanics license from the province.

He met Mary, his wife-to-be, who had also attended the school for the blind. They worked hard, married, secured a loan to buy a house, and raised a family of three children.

He went on to have a long and successful career as a highly valued mechanic. With one particular employer over 25 years, he rarely missed a day of work. His career led him to a passion for owning and restoring antique cars. In 1953, he hitch-hiked to New Brunswick to buy a 1927 Springfield Rolls-Royce Phantom meant as a parts-only car; but within a few years, he had it in good working order. Two years later, the Rolls-Royce was featured in the National Day Parade in Halifax. Eric was remembered by friends and colleagues as a good-natured, responsible man who laughed often.

During his retirement years, he was an avid blood donor, a square dancer, a ham-radio operator, a CBC radio fan, and an involved citizen in his community. He was a rare person who took the time to send thank you notes whenever his pension was increased over the years. He was grateful for his life and saw it as a gift – to be paid forward. He urged his children never to give up on their dreams.

“Life holds very great happiness and interest for me,” he said; “99 more years would be too short for all the different things I have in mind to do.”

There is much more to this man’s story, but the essence of the book gave me a sense of the tangle of complexities around the Halifax explosion, and one human being’s choice to live a productive, happy life. I admired Eric’s well-thought-out decisions and his determination.

If you want to read about the results of a life-long can-do attitude, I recommend The Blind Mechanic – a beautifully written book by a proud and loving daughter.

Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB)

Position Statement on

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID),

Regarding the Blind

Position Statement

The Canadian Federation of the Blind deplores any attempts by those responsible for decision making in the Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) program to consider impending blindness as a potential reason to end a life. In the case of blind individuals, employing MAID is a stark example of the common, and tragic, misunderstanding of blindness and its consequences. Adjustment to blindness is difficult, and blind people face their own particular challenges, but it is well known that these challenges can be met, and the technology and services available today have vastly improved prospects for the blind. That someone facing blindness might want to die is tragic; that the state might sanction and aid the suicide of blind people is a total betrayal of trust and decency. The Canadian Federation of the Blind invites any blind person or their supporters to connect through our email group or our contact form and we will be here to support. We also stand willing to actively oppose this program and its devastating ramifications for the blind

Some comments concerning MAID from CFB’s listserv, December 2022:

“I believe this is an existential threat to anyone who may become blind in the future, since people who are just learning about blindness are often frightened and sometimes despairing. If we can’t get to them before the assisted suicide doctors do, we will be witness to the deaths of many people who could live wonderful lives. I think all of us know at least one person who thought blindness would make their existence miserable and have learned better because of what we have to offer them. The CFB must speak out about this. Here is a very long article, but well worth reading…This writer provides a great deal of data that we can use to combat MAID.” ~ M.E.G.

Article: “No Other Options”, The New Atlantis: https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/no-other-options

“It seems that when fear drives our decisions we don’t always come to the best solutions, and the fear of blindness, usually exacerbated by a lack of blind role models when most critically needed, could be just such a crossroad that too many will face alone, or with the wrong advice or support available. We know that quality, timely and peer-driven rehab supports in Canada are drastically lacking, and those lacks might well drive too many newly blinded individuals to Trudeau’s MAID for relief.” ~ A.R.

“This is an extremely troubling issue, but we encourage everyone to make themselves aware of what’s going on. Now more than ever, positive messages about blindness are needed in communities all across Canada.” ~ E.B.

“It is a serious discussion, for all of us.” ~ G.B.

“I would like to commend the executive for drafting such an excellent message regarding this extremely important and difficult issue. I completely agree with your statement. Thank you for writing it. This is an issue that has troubled me for a long time. I feel sick to my stomach when it is brought up, but it must be dealt with, and it must be dealt with in a straight, aggressive manner. Very well done.” ~ E.L.

“Thank you for taking a stand on such a bad law. Count me in to help as I can to say “no” to this horrible law that can hurt many of us… MAID is dangerous and needs to be stopped or we all are in big trouble moving forward for the future.” ~ M.K.

Another article about MAID: “Killing fields of liberal Canada: Shocking figures reveal thousands including those who aren’t terminally ill are choosing to end their lives”, The Daily Mail: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11548029/Killing-fields-liberal-Canada-Shocking-figures-reveal-thousands-choosing-end-lives.html

Custodialism: A Form of Colonialism

by Elizabeth Lalonde

Editor’s note: The article below is a university assignment posting written by Elizabeth for a master’s degree course.

Posting three

“Colonialism is about imposing a world view, a set of values and ideas about how things ought to work, and an agenda for development, on a group, community or society” (Ife, 2013, p. 185).

In this posting, I am compelled to discuss the disability movement and its experience of colonialism. In the context of disability, I would define colonialism as custodialism, a form of oppression unique to people with disabilities. Custodialism is similar to colonialism in that it involves domination of one person or group of people over another and the person or group with the power believes their lives are innately better than the lives of the people they are “taking care of”. Wiktionary defines “custodialism” as “an approach to caring for people in institutions which emphasizes supervision and control over the inmate’s environment and access to resources.”

The idea that a non-disabled person is more fortunate, more able, or more competent than a person with a disability is so entrenched in our society that people usually do not even recognize it. Ife says colonialism can be subtle and can be unconscious. “All it needs is for a community worker to believe that they in some way have a superior world view, are more enlightened, have more education, more wisdom or more expertise, and that their opinion counts more than the opinions of those with whom they are working,” (Ife, 2013, p. 196).

But the colonial way of thinking goes even deeper than feelings of superiority on the part of the non-disabled community worker. The attitude of most non-disabled people and even many people with disabilities is that not having a disability is always, and obviously, better than having a disability. This idea is so ingrained in mainstream ethos that when this belief is challenged, people are often affronted and taken aback.

For example, people are usually stunned when I mention that I am not interested in a “cure.” I have always lived as a blind person; it is part of my identity and way of life.

It is a misnomer that someone who has been blind since birth would be better off with sight. The movie At First Sight (1999) portrays the life of a blind person who had surgery that gave him vision. The movie talks about how his brain could not cope with the enormous amount of visual stimuli he received, and he was not able to recognize objects unless he touched them first. His brain did start to adapt slowly, though in the end, he lost his vision.

This isn’t to say there aren’t definite advantages to being able to see. Of course there are. But there are also advantages to not being able to see. I can do certain things that sighted people cannot do because I have practiced the skill in a non-visual way.

I am not arguing the rightness or wrongness of this way of thinking. I just want to point out that there can be many different perspectives, which Ife says is a post-modernist approach (Ife, 2013).

Another way in which custodialism, or colonialism, dominates in the realm of disability is when specialists, particularly sighted or non-disabled experts think they know what is “best for us”. Ife describes this restrictive approach well when he discusses the enlightenment world view that claims the only valid knowledge comes from the top down (Ife, 2013).

The field of orientation and mobility (O&M) provides an excellent example of this phenomenon. Note: “O&M is a profession specific to blindness and low vision that teaches safe, efficient, and effective travel skills to blind people.” Colleges that teach this vocation, historically have banned blind people from becoming certified; in fact, this is still the case in many of these programs.

The prevailing belief of sighted experts is that it is “unsafe” for a blind person to teach another blind person how to get around, even though blind people have been teaching blind people since the world began. What they don’t realize is that blind people teach each other using an entirely different approach. Instead of using our eyes to teach people, we use non-visual methods, such as staying in close physical contact with a learner while traveling or crossing a street, calling out to one another, demonstrating hands-on techniques, etc.

In response to the discrimination of the traditional O&M specialists, a group of blind activists developed their own blind-lead master’s program where blind people can become cane travel instructors. Sighted people can as well, though they have to train under blindfold (Professional Development and Research Institute on Blindness). This revolutionary program represents what Ife would call a bottom-up approach, a grassroots movement of collective action (Ife, 2013).

The Louisiana Tech program promotes using a much longer and lighter cane because a longer cane provides more advanced warning of obstacles and allows a blind person to walk faster and more safely. Traditional sighted instructors often adamantly oppose these longer canes; one actually became quite angry at me when he discovered I was using one.

The custodial attitude is also obvious in the teaching of Braille. Many teachers of the blind refuse to teach their students Braille, particularly if the student has some residual vision, because of the custodial or colonial mindset that Braille is inferior to print and “too hard to learn.” I could write many essays on why this is not true, but in short, with practice many blind people can read as fast or faster than sighted people.

The colonial community worker approach is also rampant in the disability world. For example, I ski with a guide who skis behind me and gives me directions. I am an intermediate skier. There is an organization that supports people with disabilities to ski, an extremely helpful program. However, they tend to use a “custodial” approach, where the disabled skier is not on an equal level to the guide/instructor. I recently went skiing with my family. When I met my guide, they overwhelmed me with how they were going to help me and how they knew what I needed and they talked to me as if I had never been anywhere on my own, let alone on a mountain. When I reacted to them by letting them know very directly that I knew how to ski and that I could take care of myself and that I just needed them to be my guide, they became almost angry and definitely agitated. I face this kind of attitude more often than not, and sometimes it affects my self esteem if I let it.

The idea that because we have a disability, we need to “be taken care of” is pervasive. a common English saying related to blindness that expresses this custodial attitude perfectly is “the blind leading the blind.” This expression is belittling. At a blindness convention several years ago, I was part of the planning team. We boldly decided the theme would be “The Blind Leading the Blind.” Of course we turned the cliche on its head by demonstrating in words and action how we can and do take care of ourselves and each other.

The history of disability is full of examples of oppression. ADL, an anti-discrimination collective in the US, published a backgrounder in 2017 called A Brief History of the Disability Rights Movement. It states that in the 1800s, for instance, people with disabilities were treated with scorn and were unable to contribute, “except to serve as ridiculed objects of entertainment in circuses and exhibitions” (ADL, 2017). The backgrounder goes on to say that people with disabilities “were assumed to be abnormal and feeble-minded, and numerous persons were forced to undergo sterilization” (ADL, 2017). It also states that many disabled people were put into institutions and asylums for life. Institutionalizing people with disabilities has often been viewed as “merciful” by the mainstream. However, this treatment “ultimately served to keep people with disabilities invisible and hidden from a fearful and biased society (ADL, 2017).

The history of custodialism in Canada could be a paper in itself. In 2012, my colleague, Graeme McCreath, wrote a book called The Politics of Blindness: From Charity to Parity on this topic. I encourage people to read it.

As you can tell, I could go on for pages about custodialism and its impact on people with disabilities. But I am already far over the word limit! This posting makes me realize how much I want and need to explore the topic in more depth.

I haven’t really answered the question about how colonialism affects my own practice of community development. I will say briefly, that knowing first-hand what it is like to feel inferior and insignificant because of how I am treated by people who have a custodial approach, I want to make sure that I do not treat other people and groups in this way. I also have to be careful not to impose my own bias of “being okay with blindness” on other blind and low vision people. Everyone has their own journey in regards to conditions in their lives, and it is inappropriate and harmful to push my own way of thinking on another person. If people are to come to a more positive perspective of their blindness / disability, they must arrive at this point in their own time and in their own way.

https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/brief-history-disability-rights-movement

Ife, J. (2013). Community development in an Uncertain World Vision, Analysis and Practice.

McCreath, G. (2012). THE POLITICS OF BLINDNESS: From Charity to Parity

www.thepoliticsofblindness.com

Vision Aware.

https://visionaware.org/everyday-living/essential-skills/an-introduction-to-orientation-and-mobility-skills/

Professional Development and Research Institute on Blindness

https://www.pdrib.com/index

Wiktionary: https://en.wiktionary.org › wiki › custodialism

Dr. Marc Maurer: Discriminatory Comments

Triggered His Advocacy

(HISTORICAL)

Editor’s note: The 7th general assembly of the World Blind Union (WBU) met in Geneva, Switzerland, August 15 – 23, 2008. Below is a quote from a speech delivered there by Dr. Marc Maurer, who was president of the US National Federation of the Blind (NFB), the world’s largest movement of blind people, from 1986 to 2014.

CFB was honoured to host Dr. Maurer and his wife Patricia at our 2007 ‘Moving Forward’ convention in Victoria, BC.

Dr. Maurer works as an attorney specializing in civil rights law and issues related to blindness. During his lifetime he has faced his share of discriminatory treatment. No one seems to be immune to society’s old stereotypes, misconceptions and lack of knowledge about the abilities of blind people. Here he offers one example of an experience he had while a student in law school and how it helped energize him and shape his future:

Despite all of the evidence that blind people possess ability, the capacity of the blind has routinely been written off. Decades ago, when I was studying law, I found myself one evening in a class on American tax law. The portable talking calculator had just been invented, and I had one of them to use for tax calculations. I decided to show it to my professor. I thought he might find it of interest since it was the newest breakthrough in technology for the blind.

As I placed the talking calculator on the professor’s desk after the class had been dismissed, and as I performed a calculation, he said in an offhand way, “That’s interesting.” Then he added, “By the way, what are you doing in this class?” I was startled by the question. I had imagined that students sign up for classes to learn about the subject matter being taught. I recognize that taxation is not a course of study that would stimulate everybody, but I have always thought that the management of money is a useful thing to know. Consequently, when the professor asked the question, it took me by surprise. However, he did not let me answer. He said, almost without a pause, “Oh, some of this will be useful in your divorce cases.”

In the vernacular in the United States, it was a put-down. The professor did not expect me to be able to handle more than the rudimentary elements of the taxation course. He did not expect me to be an expert in the subject he was teaching. He did not expect me to be able to handle complex legal matters. He assumed that the non-complicated routine portions of the law would be all that I could do. This comment is one of the elements that caused me to concentrate on advocacy and civil rights. This comment made me believe that I should challenge the assumptions of those in society who think that the blind have little ability and less will. This comment helped me decide that I should fight back.

A Definition of Blindness

by Kenneth Jernigan

Editor’s note: We all recognize the legal, medically-measureable definition of blindness, which yays or nays one’s eligibility for government or workplace programs, services and benefits. This measure of blindness is: acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye and being uncorrectable; and/or 20 degrees or less in visual field.

Also, attempts have been made by professionals to hierarchy one’s level of blindness with language like legally blind, visually or sight impaired, partially sighted, visually disabled or challenged, and maybe a few others, which are used interchangeably with the word blind. As Elizabeth Lalonde, past president of CFB, says in her article titled, “Back to Blind” (The Blind Canadian, Vol.1; also reprinted in this issue), she got tired of the confusing jargon around blindness and what to use and where to fit in. She decided to just use the word ‘blind’. And many of us have.

Dr. Kenneth Jernigan, was president of the U.S. National Federation of the Blind (NFB), the largest movement of blind people in the world, between 1968 to 1986. He was an active leader of the organization right up to his death in 1998. He explains a smart, more holistic definition of blindness where blindness “must be defined not medically or physically but functionally.” Here is what he says:

Before we can talk intelligently about the problems of blindness or the potentialities of blind people, we must have a workable definition of blindness. Most of us are likely familiar with the generally accepted legal definition: visual acuity of not greater than 20/200 in the better eye with correction or a field not subtending an angle greater than 20 degrees. But this is not really a satisfactory definition. It is, rather, a way of recognizing in medical and measurable terms something which must be defined not medically or physically but functionally.Putting to one side for a moment the medical terminology, what is blindness? Once I asked a group of high school students this question, and one of them replied – apparently believing that she was making a rather obvious statement – that a person is blind if she “can’t see.” When the laughter subsided, I asked the student if she really meant what she said. She replied that she did. I then asked her whether she would consider a person blind who could see light but who could not see objects – a person who would bump into things unless she used a cane, a dog, or some other travel aid and who would, if she depended solely on the use of her eyesight, walk directly into a telephone pole or fire plug. After some little hesitation the student said that she would consider such a person to be blind. I agreed with her and then went on to point out the obvious – that she literally did not mean that the definition of blindness was to be unable to see.

I next told this student of a man I had known who had normal (20/20) visual acuity in both eyes but who had such an extreme case of sensitivity to light that he literally could not keep his eyes open at all. The slightest amount of light caused such excruciating pain that the only way he could open his eyes was by prying them open with his fingers. Nevertheless, this person, despite the excruciating pain he felt while doing it, could read the eye chart without difficulty. The readings showed that he had “normal sight.” This individual applied to the local Welfare Department for Public Assistance to the Blind and was duly examined by their ophthalmologist. The question I put to the student was this: “If you had been the ophthalmologist, would you have granted the aid or not?”

Her answer was, “Yes.”

“Remember,” I told her, “under the law you are forbidden to give aid to any person who is not actually blind. Would you still have granted the assistance?” The student said that she would. Again, I agreed with her, but I pointed out that, far from her first facetious statement, what she was saying was this: It is possible for one to have “perfect sight” and still in the physical, literal sense of the word be blind.

I then put a final question to the student. I asked her whether if a sighted person were put into a vault which was absolutely dark so that he could see nothing whatever, it would be accurate to refer to that sighted person as a blind man? After some hesitation and equivocation the student said, “No.” For a third time I agreed with her. Then I asked her to examine what we had established.

1. To be blind does not mean that one cannot see. (Here again I must interrupt to say that I am not speaking in spiritual or figurative terms but in the most literal sense of the word.)

2. It is possible for an individual to have “perfect sight” and yet be physically and literally blind.

3. It is possible for an individual not to be able to see at all and still be a sighted person.

What, then, in light of these seeming contradictions is the definition of blindness? In my way of thinking it is this: One is blind to the extent that the individual must devise alternative techniques to do efficiently those things which he would do if he had normal vision. An individual may properly be said to be “blind” or a “blind person” when he has to devise so many alternative techniques – that is, if he is to function efficiently – that his pattern of daily living is substantially altered. It will be observed that I say alternative not substitute techniques, for the word substitute connotes inferiority, and the alternative techniques employed by the blind person need not be inferior to visual techniques. In fact, some of them are superior. The usually accepted legal definition of blindness already given (that is, visual acuity of less than 20/200 with correction or a field of less than 20 degrees) is simply one medical way of measuring and recognizing that anyone with better vision than the amount mentioned in the definition will (although he may have to devise some alternative techniques) likely not have to devise so many such techniques as to alter substantially his patterns of daily living. On the other hand, anyone with less vision than that mentioned in the legal definition will usually (I emphasize the word usually, for such is not always the case) need to devise so many such alternative techniques as to alter quite substantially his patterns of daily living.

It may be of some interest to apply this standard to the three cases already discussed:

First, what of the person who has light perception but sees little or nothing else? In at least one situation he can function as a sighted person. If, before going to bed, he wished to know whether the lights are out in his home, he can simply walk through the house and “see.” If he did not have light perception, he would have to use some alternative technique — touch the bulb, tell by the position of the switch, have some sighted person give him the information, or devise some other method. However, this person is still quite properly referred to as a blind person. This one visual technique which he uses is such a small part of his overall pattern of daily living as to be negligible in the total picture. The patterns of his daily living are substantially altered. In the main he employs alternative techniques to do those things which he would do with sight if he had normal vision — that is, he does if he functions efficiently.

Next, let us consider the person who has normal visual acuity but cannot hold his eyes open because of his sensitivity to light. He must devise alternative techniques to do anything which he would do with sight if he had normal vision. He is quite properly considered to be a “blind person.”

Finally, what of the sighted person who is put into a vault which has no light? Even though she can see nothing at all, she is still quite properly considered to be a “sighted person.” She uses the same techniques that any other sighted person would use in a similar situation. There are no visual techniques which can be used in such circumstances. In fact, if a blind person found herself in such a situation, she might very well have a variety of techniques to use.

I repeat that, in my opinion, blindness can best be defined not physically or medically but functionally or sociologically. The alternative techniques which must be learned are the same for those born blind as for those who become blind as adults. They are quite similar (or should be) for those who are totally blind or nearly so and those who are “partially sighted” and yet are blind in the terms of the usually accepted legal definition. In other words, I believe that the complex distinctions which are often made between those who have partial sight and those who are totally blind, between those who have been blind from childhood and those who have become blind as adults are largely meaningless. In fact, they are often harmful since they place the wrong emphasis on blindness and its problems. Perhaps the greatest danger in the field of work for the blind today is the tendency to be hypnotized by jargon.

Back to Blind

by Elizabeth Lalonde

Editor’s note: Elizabeth was a longtime president of CFB and is director of the Pacific Training Centre for the Blind. This superb article was originally published in Volume 1 of The Blind Canadian in 2002. It is valuable to read and to take a look at the language around blindness. Through the Federation we know that blindness and the word “blind” is respectable and nothing to be ashamed of.

As a little girl, I called myself visually impaired. My tongue twisted around the awkward words, and people’s minds twisted around their meaning. The words signalled vision of some sort, but how much, how clear? Could I see colour, detail, classmates’ fingers held in front of my face? Maybe I could see more than that. Maybe all I needed was a pair of glasses.

When I tired of “visually impaired,” I tried the old standby: “I can’t see very well,” my little girl’s voice, shy and high-pitched as I looked sideways at my teacher. Well, the words “I can’t see very well” earned me a desk in the front row and the chance to stand close to the teacher while she wrote times tables on the chalkboard. But that’s all they earned me.

These days there is a trend to use terms that reflect the degree of sight a person has. Phrases such as visually impaired, sight impaired, partially sighted, visually challenged, visual disability and so on cloud our lexicon of blindness language. People choose from this hodgepodge of words and phrases to avoid the term we in the Canadian Federation of the Blind are proud to use: “blind.”

Substitutions for the word “blind” are common in the blindness community. Organizations publish Canadian blindness literature with titles that contain words like vision and sight. Organizations and support groups for blind people also commonly have visual names.