The Blind Canadian is the flagship publication of the Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB). It covers the events and activities of the CFB, addresses the issues we face as blind people, and highlights our members. The Blind Canadian:

• Offers a positive perspective and philosophy on blindness

• Serves as a vehicle for advocacy and protection of human rights

• Addresses social concerns affecting the blind

• Discusses issues related to employment, education, legislation and rehabilitation

• Provides news about products and technology used by the blind

• Tells the stories of blind people

• Covers convention reports, speeches, experiences

• Archives historical documents

EDITOR: Doris Belusic

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Kerry Kijewski

PREPRESS, PROOFREADING & WEB DESIGN: Sam Margolis

The Blind Canadian, published by the Canadian Federation of the Blind, comes out twice annually in print and on www.cfb.ca in web and pdf versions

The Blind Canadian welcomes articles, resources and letters to the editor for possible publication.

We thank Victoria Foundation and the Federal Government for a generous grant which helps fund this educational outreach magazine.

Canadian Federation of the Blind

Douglas Lawlor, President

PO Box 8007

Victoria, BC, V8W 3R7

Phone: (250) 598-7154 Toll Free: 1-800-619-8789

Email: editor@cfb.ca or info@cfb.ca

Website: www.cfb.ca

Find us on Facebook

Twitter: @cfbdotca

YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/CFBdotCA

President’s Message

Photo credit: Daryl Jones

Since I was elected as CFB president in May at the CFB Annual General Meeting, 2022 has been an interesting experience and year for me, that’s for sure.

Firstly, CFB held its convention ‘Positive Outlook’ in May, this being the second year we put it on via Zoom.

Secondly, in regards to our human rights case, I visited Victoria, BC in March to check out the dangerous hardscape bike lanes that prevent blind people from independently and safely accessing bus stops that are now situated out on floating islands along Pandora Ave and Wharf St.

Among the main problems I saw in regard to the floating bus stops are, if you have hearing loss or the traffic volume is high, as it usually is on that busy arterial, you will not hear approaching bicycles while you wait for the yellow flashing light to change in your favour. And the fact that the audio pedestrian system gives a message saying that vehicles may not stop, seems to me that the City does not want to enforce a bylaw saying vehicles, including bicycles, must stop for pedestrians, and are using this audio message as something that will protect them legally in case someone gets hit.

Another problem I saw was that it was not easy to locate the tactile plate for the crossing when walking. The City should have extended that tactile plate so it is easy for anyone using a cane to find.

Thirdly, I attended my first in-person US NFB national convention, which was held in New Orleans in July. Due to the pandemic, I have only attended previous NFB conventions online via Zoom. So, this was different, a big deal.

Attending the convention in person was a very enjoyable experience. I met lots of people from different states. I even met some people I would chat with online over the years. Due to the COVID testing situation, I did not get to attend all of the things I wanted to, because I had to get a COVID bracelet, which I didn’t know about until the next day.

I really enjoyed the events that I did get to attend. I attended a guide dog seminar and learned that people are having the same discriminatory problems with public transportation and guide dogs as we are in Canada.

I really enjoyed a session on estate giving. This is where a person wishes to leave something for an organization in their will.

I also attended a session on the performing arts and how this relates to the blind. This focused on blind people narrating audio description for film. I even heard some live examples of people doing this. It was truly something to hear.

I cannot forget the Exhibit Hall. This is a large conference room that is absolutely full of people. Don’t be afraid of crowds here. You will get to meet all of the vendors in the blindness industry, both low and high tech. I was interested in braille displays this year, so spent a lot of time looking at the braille displays and note takers on offer. You can even purchase products directly at the convention if you are so inclined.

If you attend one thing, I highly recommend the NFB general sessions. You can get a condensed version, with many of the speakers who have presented full seminars in the previous couple of days. Be prepared to do a lot of sitting at these sessions. People are presenting one after the other here. Interesting, informative and inspiring!

If I could give some advice, be prepared before you go. Make sure you have your passport and medical insurance. Medical insurance can usually be purchased when you book your airline ticket. The last thing you want is to have a medical emergency in the United States and suddenly realize that it’s not covered on your Canadian medical card.

Also, try to arrive to convention a day early if you can, so you can take care of anything that may arise, as well as get the feel for the venue. These venues are very, very big places and can take some time to get used to. You will be dealing with lots of people at any one time, moving from place to place.

One of the things I didn’t realize was that I was being charged an exorbitant amount of money for cell service from my Canadian carrier. I ended up going to a T-Mobile store and purchasing a SIM card for $60 US that gave me unlimited data for a month. It was certainly cheaper than paying the high prices my carrier wanted for something like 250 MB of data. The way I use data, I would go through that in no time. The sad thing is I lost a day of convention because I had to get this taken care of. If I had arrived a day early, I would have taken care of it before the convention started.

Would I go to one of these conventions again? The answer would be a resounding “YES!” The NFB national convention has something for every interest. So if you go, you will certainly take away something different than I did, because our interests may be different.

I am looking forward to the new year. Three major things I see that the CFB needs to focus on in 2023 are membership, fundraising and employment, as well as our usual advocacy, mentoring and conventions.

I think the biggest challenge for us this year will be to get more members into the organization. I would like to focus on the western provinces, mainly Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

Fundraising. We really need to fundraise. We are always looking for ideas from anyone regarding this.

I am looking for a couple of people, so we can put together an employment committee. Given the layoffs we are experiencing in the technology industry, and the economic situation that I think we are going to see in the next few years, we really need to get generating ideas for employment. If there is one thing we all know as Federationists, we can be the first to be let go from a job when the economic situation changes.

Here’s looking forward to our new year 2023.

The Blind Canadian Magazine

Celebrates 20th Anniversary!

The Blind Canadian is currently published twice annually and is geared towards the general public and the blind alike.

History

The first issue of The Blind Canadian was published in 2002 with Elizabeth Lalonde as originating editor.

In 2008, with Volume 3, I took up the role as assistant editor. In 2009, I filled in as editor on Volume 4 – a special digital edition that honoured Louis Braille on the 200th anniversary of his birth. Then in 2013, with Volume 6, I began in earnest as The Blind Canadian editor.

CFB self-published the first four volumes. Then between 2012 and 2019, beginning with Volume 5, CFB published the magazine through a contract with Jack and Shirley Hyman of Public Sector Publications. Thanks to Paul and Mary Ellen Gabias, who had worked with them on a previous blindness magazine, we got the new project underway. CFB produced the articles and the company looked after digital layout, printing and mailing of 2,000 copies, as well as providing CFB with a digital copy that we uploaded to CFB’s website for online reading. The company also looked after the business end of things, including advertisements in the magazine.

Things changed with the onset of Covid and partnership with Public Sector Publications came to an end. From then on, CFB has been fully producing each volume of The Blind Canadian, in both print and digital formats, although print copies are restrictive in numbers now due to high cost. We encourage online reading of The Blind Canadian on CFB’s website, www.cfb.ca under “Publications”, available in either pdf or web versions.

We have had several assistant editors over the years and currently Kerry Kijewski is in this role. Almost from the beginning, Sam Margolis has looked after proofreading and the uploading of our online magazine, in both PDF and web versions, to CFB’s website. When the Hymans stopped working with us, Sam began a wider role, doing prepress layout, proofreading and everything it takes to get the magazine uploaded in the two digital versions, plus, get it ready for the few print copies we do. We still send every volume of The Blind Canadian to Library and Archives Canada so the magazines get preserved for future generations, and a copy also goes to the NFB’s International library.

Many things have happened and have been written about since the magazine’s inception.

What’s The Blind Canadian About?

The magazine addresses a wide range of topics and issues important to blind Canadians. There are loads of informative and inspirational articles, and it also covers events and activities of CFB.

The Blind Canadian:

• offers a positive perspective and philosophy on blindness

• serves as a vehicle for advocacy and protection of human rights

• addresses social concerns affecting the blind

• discusses issues related to employment, education, legislation, rehabilitation

• provides news on products and technology used by the blind

• tells the stories of blind people

• archives information and historical documents

The magazine contains:

• CFB and NFB convention reports

• many CFB convention speeches by blind individuals, and our presidents’ convention addresses and banquet speeches, which are often transcribed into print from audio recordings.

The magazine also has articles on human rights cases that we’ve been involved with, such as:

• dangerous bike lanes that create inaccessible floating bus stops

• guide dog / taxi discrimination

And the magazine covers other advocacy issues that affect us, such as:

• the need for accessible technology

• the need for proper, government-funded, intensive blindness-skills training

• the issue of employment

• the library services issue

• and more!

Sometimes we reprint, with permission, relevant newspaper articles that deal with blindness topics or that involve one or more of our CFB members. We’ve reprinted articles from media such as the Times Colonist, CBC News, The Canadian Press, The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, Richmond News, Black Press Media and CTVNewsVancouverIsland.ca. We’ve also reprinted from places like the National Braille Press blog and the NFB Braille Monitor.

And, at the end of most volumes are recipes! Recipes like Mary Ellen’s Famous Lasagna, Creole Praline Yam Casserole, Bacardi’s Rum Cake, Scottish Shortbread, and in this volume, Chili and Pumpkin Spice Cake with Cream Cheese Frosting. After all, many blind people are great cooks!

13 Featured Articles

Below is a sampling of the many great articles found in various volumes of The Blind Canadian. I’m featuring 13 pieces which are among our best. Again, you can read these and more at www.cfb.ca under “Publications”.

1.

Volume 13

“Free as a Butterfly: My Blindness Rehabilitation Journey”, by Gina Huylenbroeck.

This article by Gina is very informative and inspirational, detailing her nine-month journey receiving intensive blindness-skills training at the Louisiana Center for the Blind in the US. It describes well all that a student goes through over a nine-month period in order to gain the best all-round blindness and life skills.

2.

Volume 5

“My Journey at the Louisiana Center for the Blind”, by Elizabeth Lalonde.

This article by Elizabeth is another valuable, interesting piece, detailing her own nine-month intensive blindness-skills training experience at Louisiana Center for the Blind.

3.

Volume 16

“Blind People in Charge: Ring the Freedom Bell: Pacific Training Centre for the Blind”

At many CFB conventions we hear speeches, like this one, given by Elizabeth Lalonde, director of the Pacific Training Centre for the Blind (PTCB) and from her students in the Blind People in Charge program. Students tell their inspiring stories of success. This article, and the ones sprinkled throughout various volumes of the magazine are very interesting and inspiring. Search the others out. They’ll be well worth the read. These speeches have been transcribed into print from audio recordings.

4.

Volume 16

“One Vision, One Cane, One Dream: My Work in India”, by Anna Tolstaya.

This is a convention speech given by Anna, a past-PTCB student.

She spoke about how timid she used to be, but after blindness-skills training at PTCB. She had gained confidence and skills and ended up travelling solo to volunteer in India.

5.

Volume 15

“What Does ‘Blind’ Have To Do With It? The Right to Parent From a Sighted Daughter’s Perspective”, by Joanne Gabias.

Growing up as one of four children to blind parents, Joanne’s speech, presented at the US National Federation of the Blind (NFB) convention, is an informative, very interesting story about growing up with blind parents and the normality of it.

6.

Volume 9

“Living the Life You Want is for Blind People Too”, by Gary Wunder.

Gary is editor of NFB’s leading magazine, The Braille Monitor. He was a guest speaker at CFB’s 2014 convention on Bowen Island, BC and gave this super interesting and inspiring speech about his life as a blind person.

7.

Volume 9

“Johnny Tai – Martial Artist”, by Johnny Tai.

Johnny, a blind martial artist, gave this very interesting and inspiring speech at CFB’s 2014 convention held on Bowen Island, BC. He talked about his life as a blind child and adult, and about winning gold at the International Tiger Balm competition against sighted opponents, therefore earning a spot to compete at the Olympics.

8.

Volume 17

“Arrested While Wanting to Grab a Cup of Coffee”

This story of discrimination, told by Ben Fulton, a blind lawyer, is about being arrested in a gas station convenience store in BC while trying to buy a cup of coffee. The store owner did not want Ben’s accompanying guide dog in the store – and to boot, the police over-reacted with handcuffs, saying they didn’t realize the dog was a guide dog (even though it was in harness!). This article is a transcript of an interview by blind siblings, Brian and Kerry Kijewski, from their radio show, Outlook on Radio Western, aired through the University of Western Ontario.

9.

Volume 19

“The Sky’s the Limit, Outlook on Radio Western – 100th Episode”

This is another great interview by Brian and Kerry Kijewski from their radio show, Outlook on Radio Western. They have a very interesting conversation with Sky Mundell about his life, his disabilities including blindness, his work as a technology trainer at the Pacific Training Centre for the Blind, and his accomplishments as a pianist in Victoria, BC, having won Vancouver Island’s Got Talent in 2011.

10.

Volume 14

“NFB Song ‘Live the Life You Want’”

An article about NFB’s latest theme song, “Live the Life You Want” and a link to hear this inspiring, catchy tune!

11.

Volume 18, Special Edition

“CNIB: Canada’s 100-Year Monopoly”

In 2020 we published this important report, researched and written by Daryl Jones, which exposes CNIB’s monopolistic hold over the blindness business in Canada – and discusses the resulting negative consequences for the blind. After 100 years, the whole scene for blind Canadians should be much better. This report was sent to the Competition Bureau of Canada.

12.

Volume 21

“CFB: An Embodiment of the NFB – Why Does CFB Have Ties With NFB?” by Erik Burggraaf.

Erik articulates very well, in an honest, informative way, the relationship between the US National Federation of the Blind and our Canadian Federation of the Blind. He tells why we deeply value and are benefitted by our association with the NFB and their members, but also that CFB is still its own organization, fully run by blind Canadians, and not in any way in NFB’s back pocket.

13.

Volume 20

“Making Choices, Setting Goals: Look Higher, Think Broader, Dream Bigger”, by Mary Ellen Gabias.

This is a very interesting, motivational convention banquet speech given by Mary Ellen in her last term as CFB president.

Celebrating 20 Years

To celebrate The Blind Canadian’s 20th anniversary, we held a narrative nonfiction writing contest several months ago. Graeme McCreath’s submission was the winning entry and he received a $300 prize, kindly donated by a CFB supporter. Congratulations Graeme! You will find his article following this one.

A Thank You

Thank you to all who have participated in the writings and makings of this magazine over the past two decades. It is truly a valuable piece of work and is one of the best resources available in Canada on all aspects of blindness.

Submissions

We accept submissions for possible publication. Please email to:

editor@cfb.ca

I Am a Blind CFB Member Who Dreams…

(Winning Entry, CFB Nonfiction Writing Contest)

Graeme, originally from Liverpool, UK, immigrated to Canada as a young blind adult. In the UK he worked as a secretary for British Aeronautics, then trained and worked as a physiotherapist. In Victoria, BC, he worked as a physiotherapist in the hospital setting until he, along with his wife Christine, opened and ran their own physiotherapy practice for many years while raising their three children. Now in retirement, besides helping to look after grandchildren, Graeme is still working hard as an advocate for the blind, having spent many years as a CFB member and on the executive board. He is instrumental in several discrimination human rights cases involving taxi driver discrimination against guide dogs, as well as with the Victoria dangerous, poorly-designed bike lane infrastructure which has caused inaccessible floating-island bus stops. He won a case some years ago in Victoria which changed accessibility in the annual Times Colonist 10K run. Graeme is also the author of the book, The Politics of Blindness.

Below is Graeme’s winning article.

I am a blind CFB member who dreams about a time when blind Canadians are valued for their abilities, not devalued for their limitations. A time when we receive the equivalent respect and recognition as our fellow citizens. When we are defined as ordinary Canadians, who command the resources to produce productive participance. A time when we have the technology to be instantly aware of unfamiliar surroundings. When the public view us as worthy equal peers, giving us the courtesy to travel barrier free. Society can gain in celebrating people’s differences, embrace alternatives in attaining the same goals, free from social stigma. Blindness should not be what defines someone, rather, their individuality and innate abilities. A book should be defined by its contents, not it’s cover.

My very first introduction to inappropriate and derogatory comments from members of the public occurred in the summer of 1965 while growing up in the U.K. This profound prejudicial remark has remained etched in my memory. Being 18 and still a boarder at a residential school for the blind, I wanted to be constructive with my extended summer holiday time at home. The public’s persona of blindness hit me square in the face. I decided to go to the labour exchange to sign up for work. Anticipating a negative reception, my mother decided to accompany me. Arriving at the desk, we explained that I wanted to register for work. Living in the early 1960’s in a summer resort town with traditional old fashioned values, the employee announced, looking at my mother, “What on earth is he going to be employed as?” Determined to respond myself, instead of feeling like a piece of furniture being discussed, I replied, “Well, I am strong, fit and able to learn.” My mother then said, “We all pay into the system and my son is available for summer employment like all other young people his age.” The clerk reluctantly signed me up and for the next eight weeks I showed up as expected, to sign on for work. This opinionated employee deliberately avoided me each week and I never did get offered employment. Signing up, however, did qualify me for a small weekly unemployment cheque, which I suspect was the real reason for such animosity. Those with significant disabilities were devalued as burdensome baggage, unworthy of even financial support. It is entirely possible that some young naive blind person may have suffered humiliation from such an insult, but I hope, like me, they possessed the tenacity and determination to focus on the future. In fact, this incident may have prepared me for the many challenges and social barriers that we all endure. My mother taught me a valuable lesson – inclusion is a right and should not be compromised to permit discrimination.

Occasionally my blind colleagues and I have pondered how governments could be convinced to give blind Canadians the chance to qualify for a profession like physiotherapy or another practical science based profession. Such an opportunity helped change my life, while sowing the seed of blind respectability. The foresight of those influential and enlightened medical associates, who saw the potential of blind people, has allowed us the opportunity to make social inroads into obtaining employment.

In 1888, blind British citizens became one of the first to have the privilege to train as masseurs. Years later, the physiotherapy program grew from this amazing initiative, with the national examining body, the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP), embracing blind students. There were two fundamental factors that gave success to this wonderful employment niche. Ease of access, together with a sound and applicable infrastructure. Countrywide access was vital via the Department of Employment for qualifying applicants. At that time, medical schools and allied services, such as health sciences, together with nursing, were based at designated teaching hospitals. Both the academic and practical applications occurred simultaneously. The national CSP, to come in line with “modern” expectations, developed a university degree structure which, unfortunately, changed the whole dynamics. After 80 years, the North London School of Physiotherapy for the Visually Impaired closed in 1995. Since 2003, the university program has only produced one completely blind graduate.

A specific training infrastructure must be in place that recognizes our challenges and limitations. Smaller classes, more hands-on tuition [teaching], braille and talking books of related medical specialty, specially trained staff with appropriate skills and a hospital environment to support the practical aspects of training are essential to success. Once moved to the university, fees were no longer covered by the Department of Employment, basically destroying ease of access for blind students. Canada needs to show leadership with a bold approach. Specific courses, like physiotherapy and massage, could be made available through a similar U.K. Department of Employment initiative. Federal government financing with appropriate medical connections could be part of an existing university program. Such a bold move could change what it means to be blind in Canada, finally replacing the Victorian views of blindness. Our challenges are significant compared with the sighted student, and without that recognition, we shall continue to stagnate in the past. The actual cost would be completely eliminated through the substantial taxes generated after the graduating students become contributors and not treated as custodial charity recipients. Dreaming can open a window of imagination that can sometimes, like mine, change people’s lives forever. Governments at all levels need to be shown that blind people deserve to be attached to the “work bench” of life. Vital infrastructure to provide channels for blind people’s employment success needs to be developed through a direct and sustained government program.

As a vulnerable minority, blind Canadians must work to educate powerful sighted politicians. Fundamentally, if you continue to treat a group as inferior, incapable charity cases, history shows you will get the same results. Evidence is clear that when government responds to produce training and employment opportunities, this will produce a respectful, inclusive and productive work force of blind citizens. Significant challenges do, of course, require significant resources and faith in social justice. The oppressed will respond if given the chance.

CFB 2022 ‘Positive Outlook’ Convention Report:

Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB)

‘Positive Outlook’ Virtual Convention, May 6 – 8, 2022

During the first full weekend of May 2022, we put on our second year of an all-virtual convention, with people joining us on Zoom throughout the day, from across the country. It was decided that this year’s convention would entail one day of sessions and presentations – as the world begins to open up, and just maybe things can be in person again next year, after these years of Covid-19 distancing. This year’s theme was “Positive Outlook” and these words, spoken out loud, gave hope for better days ahead.

Emcees: Kerry Kijewski and Brian Kijewski

Zoom Moderator: Joanne Williams

Door Prizes: Nancy Gill

Friday, May 6 (CFB Trivia Night)

Kicking off this year’s proceedings, Trivia Master Roger Khouri put on a game of music trivia. Two teams were captained by the weekend’s MCs, siblings Brian and Kerry, for a friendly competition between two groups of CFB members.

Registered participants were eligible to win door prizes throughout the trivia evening and after presentations during the convention’s main day.

Saturday, May 7 (Presentations)

10 a.m. – 4 p.m. Pacific

The day began with opening remarks by MCs Brian and Kerry of the podcast Outlook On Radio Western and then by CFB Interim (at the time) President, Douglas Lawlor.

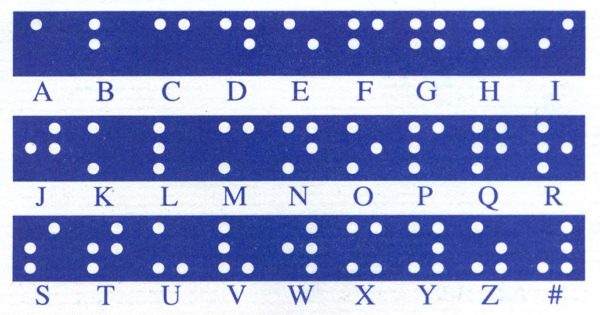

First presentation of the day was a favourite returning group, Braille Literacy Canada (BLC), presented by Jen Goulden and Daphne Hitchcock, BLC board members and leaders in the promotion of Braille.

The second session of the morning was a panel on the Accessible Digital Wayfinding Project, Vancouver Waterfront Station, presented by Colette Parras, Wayfinding professional /instructor, BCIT Bachelor of Architectural Science program; Jim Taggart, a director of Gateway navigation, editor of Sustainable Architecture and Building Magazine, and Instructor in the BCIT Bachelor of Architectural Science program; Nathan Gore, Marketing and community manager, Waymap; and David Brun, founder of Gateway Navigation, which specializes in the research, selection and implementation of audio-based navigation systems for the blind and low vision community.

Another returning guest was up next, speaking about a financial topic, always applicable, All About the RDSP (Registered Disability Savings Plan), presented by Liss Cairns (they/them), project manager, Plan Institute – Innovation. Education. Leadership.

Following a brief lunch break, kicking off the afternoon was What’s Happening on Bowen Island?: The Canadian Organization of the Blind and DeafBlind (COBD), presented by Alex Jurgensen, executive director of COBD: Camp Bowen Division; Elizabeth Lalonde, executive director of Pacific Training Centre for the Blind (PTCB); Nancy Gill, coordinator, PTC Blind and DeafBlind Seniors Roundtable; and more.

Following that, Our Rights, Advocacy, presented by Graeme McCreath, CFB leader and author of The Politics of Blindness; and Oriano Belusic, CFB first vice president.

The MCs followed with, Discussions on Diversity and the Outlook On Radio Western Podcast, Inspired by the Canadian Federation of the Blind, Outlook is a radio show through the University of Western Ontario and a podcast about accessibility, advocacy and equality, hosted by two siblings who were born blind. Presented by Kerry Kijewski, writer, blindness / disability and social justice advocate and co-host of the Outlook Podcast, along with Brian Kijewski, musician and co-host of the Outlook Podcast.

An overview and update on the organization, All About the CFB – Our Programs and How You Can Get Involved came next, presented by Douglas Lawlor, CFB interim president and Erik Burggraaf, CFB second vice president, both leaders of the national CFB, as well as CFB of Ontario.

Entertainment followed with an original song, “Real Animal” written by Maggie Bray, performed by Sky Mundell, world-class pianist, who is DeafBlind and an adaptive technology instructor at the Pacific Training Centre for the Blind; and Maggie Bray, blind artist, entrepreneur and facilitator of the CFB Kernels of Hope support group.

The day finished up with closing remarks, a final door prize of $100 and an open chat room opportunity for mingling with other convention attendees.

The weekend was rounded out by the CFB Annual General Meeting, held on Sunday, May 8.

Thanks goes out, for another year, to Elizabeth Lalonde and everyone on the planning /organizing committee for being flexible during these interesting pandemic times.

And thanks to all in attendance, because it’s those who show up that make the whole thing a true success.

Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB) Members Elect National Executive Board for 2022 – 2023

The Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB) held elections for its National Executive Board at its Annual General Meeting on May 8, 2022. It was held via Zoom. All members of the Executive are blind and serve in their positions without compensation.

This year, positions of President, Second Vice President and Treasurer were up for scheduled election. Also, due to previous position switches in Sept. 2021, Secretary and Member at Large positions were also up for election and will be one-year terms to finish off these terms.

• President: Members elected Doug Lawlor.

(For the past half year, Doug had transferred from his role as Secretary to fill in as interim President, when Mary Ellen Gabias retired from the Presidency in Sept. 2021.)

• Second Vice President: Members elected Nancy Gill.

• Treasurer: Members elected Erik Burggraaf.

• Secretary: Members elected Patrick Bouchard.

(For the past half year, Patrick had transferred from his role as Member at Large to fill in as interim Secretary, when Doug began to fill the role as interim President in Sept. 2021.)

*Please note: The position of Secretary has again become vacant as of this fall 2022 and will need to be filled again.

• Member at Large: Members elected Graeme McCreath.

(This role had been vacant since Patrick had transferred to the position of interim Secretary in Sept. 2021, to replace Doug who had filled in as interim President.)

• Immediate Past President: Mary Ellen Gabias

Congratulations and thank you to the new CFB Executive Board. We are in good hands!

Members are grateful to:

• Oriano Belusic for his continued service as First Vice President,

• Mary Ellen Gabias for her many years as President and now is Immediate Past President.

• Elizabeth Lalonde for her many years as Immediate Past President and, before that, her many years as President.

• Erik Burggraaf who served as Second Vice President before being elected as Treasurer.

• Brian Kijewski who is retiring from the position of Treasurer.

Thank you to all for your hard work, dedication and service.

The Canadian Federation of the Blind is an organization of blind people committed to the equality and empowerment of blind Canadians. Through advocacy, public education and mentoring, members work for change, promote a positive perspective on blindness and together gain confidence and skills.

Guide Dogs: Beyond the Harness

An Essay

***

She pulls, guiding him along a busy downtown sidewalk. She wears a brown leather harness strapped to her blonde fur torso with an attached sturdy handle that’s in his left hand. She walks one step ahead and guides him forward. He feels her close, her every move and follows her lead. He tells her what he wants her to do and praises her for doing it well. He wears casual pants and a long-sleeved shirt–always a long-sleeved shirt. A small canvas kibble pouch hangs from his belt. His brown hair is greying now that he is 54. She stops at the curb, so that he will, and he rewards her with a kibble.

***

I kissed my husband goodbye. His anticipation rose as the plane climbed over the Victoria, B.C. airport then headed for San Francisco. It was an early morning in August when Oriano was on his way to get a new guide dog. What would the new dog be like this time, he wondered.

Oriano was greeted at the arrival gates by a school volunteer who handed him a luxury bagged lunch holding a much-appreciated prosciutto submarine sandwich and other goodies. She drove him the one-hour trip to Guide Dogs for the Blind, located in San Rafael, where he would be a student for the next two weeks.

“Well, her name is Birch,” Oriano announced in an email to me on his second day at the school. “Don’t know who gave her that name but she is smart and cute as heck. Small frame, will fit in my pocket–55 pounds, like Hillie. Yellow lab. So far, we walked around the building and she earned at least 10 kibbles. At this rate she won’t be small for long.” He had just met Birch, his new guide dog, a few hours earlier and I could tell he was already enamoured.

Oriano wanted a guide dog that was small. This was the only request he made when the school had asked what qualities he’d prefer in a dog. He said he wanted a dog that could “fold up” while travelling–one small enough to easily fit in tiny spaces, like under a chair or at his feet on the floor of a cab. Birch definitely fit the bill.

Oriano became totally blind when he was just seven. He was picking flowers for his teacher with a friend in the forest near his Croatian village home. Had he stuck to flowers he would have been fine, but he also picked up a hand grenade. A leftover hand grenade from World War II. With his strong personality even then, he won the fight over who should open this interesting object. He knocked its lid off with a rock. Then he lost the fight. Big time. Lost his eyesight and an arm. But he lived. This was nearly 50 years ago.

A few years later he and his family moved to Canada. He has used a guide dog for most of his adult life, getting his first dog when he was only 16.

Birch is Oriano’s fourth guide dog. Like his previous three guide dogs, Birch was bred at Guide Dogs for the Blind. At eight to ten weeks old, she was weaned from her mother and spent the next one-and-a-half years with her volunteer puppy raiser family. They brought her home, raised and socialized her and taught her manners. She wore a little jacket when she went places that said “Guide Dog Puppy” so she would receive the same privileges of access as full-fledged guide dogs. She travelled on buses, trains, in a camper, and her favourite, a golf cart. She attended basketball and beach volleyball games, movies and live theatre, and church. She walked on Avila beach and boardwalks in Santa Cruz. She entered restaurants, stores, medical offices and a hair salon. She loved camping. She heard noises like sirens. This exposure to the world was crucial for her development as a guide dog. Through this she learned confidence in many situations. This is the foundation of becoming a good guide dog. “If you don’t have a properly socialized dog, you don’t have the makings of a guide dog,” Oriano told me.

When Birch’s term with her puppy raiser family was over, she returned to the school for her assessment. Some dogs do not pass past this point and do not end up as guide dogs. Certain traits are not suitable, such as nervousness, poor health, aggression, a tendency for distraction, or a lack of will to work. Instead these dogs become service dogs for other disabilities or pets with their puppy raisers. Birch passed the assessment and went on to receive two months of intensive guide dog training. She learned to be comfortable in a harness and learned how to guide a blind person. She was then matched to Oriano’s personality, lifestyle and environment and her training was tweaked for him.

That was when Oriano travelled to the school in August to get Birch and to train with her. His first training sessions with Birch were around the school building. Gradually over days they went further afield into the streets of the community. Towards the end of training, they walked mornings and afternoons in San Francisco. They walked on Fisherman’s Wharf and Oriano ate sourdough bread and chowder and bought handmade chocolates to take home.

Throughout training, Birch earned kibbles which are always kept in the pouch on Oriano’s belt. Birch is the first of Oriano’s guide dogs to be trained on treat-based positive reinforcement, instead of verbal-only praising. Oriano was not in favour of this treat-based method at first, thinking it would encourage a dog to guide only for the sake of food. But after training with Birch and getting to feel comfortable with this new way, he changed his view. It seems that kibble treat reinforcements work well.

We celebrated Birch’s second birthday this November, giving her a new nylabone to replace the one she had chewed up within the last month. Birch has already won many hearts of our family and friends and has proven to guide Oriano with perfection.

Birch looks like a blonde fur stuffie with floppy ears, attentive round brown button eyes and a pink button nose. You could think she was part monkey the way she bounces her rubber kong–bong-bong-bong–down the stairs or how she drops her rubber ring or nylabone onto your lap, wanting to tug or chew. Or you could think she was part shark, the way she stealthily circles with jaw open, ready to grab your hand ever so gently. Or that she was part cat, the way she likes to lick, always striving to reach your face. Or part chicken, when she’s stuck under the awning, defiant to step out into the rain–having never seen it in California.

Birch will often sit on our staircase, like she’s a spectator at a ball game sitting in bleachers, watching–hind legs and rump on the step above, forelegs on the step below. At times she steps up onto our treadmill and looks at us like she wants to walk. We’ve learned she was trained on a treadmill at the school. Lately she’s started to sit in front of me, with her back towards me–I finally clued in that she wants back rubs! Birch is bursting with personality, sweetness, love and kisses.

Oriano found Guide Dogs for the Blind’s facility fascinating and what it offered impressive. He said the school has been completely rebuilt and the grassy grounds are large. He toured one of the breeding houses and learned that up to 250 dogs are kept at the school at any given time. Six to eight blind students are trained every two weeks and the ratio of students to instructors is 2:1. Oriano was happy to get his own private bedroom with a bathroom and a back door that led to the dog relieving area and the playing paddocks. Oriano raved about the chef-prepared meals and fancy pastries. There was a hot tub and massages that cost one dollar a minute if you wanted. When I heard all this, the school sounded more like a resort or spa. All of a sudden I wanted to be there too–for the pampering! I learned the school is a non-profit charity, fully funded by donors. Travel, lodging, instruction and each trained guide dog–worth $45,000 – $60,000–are all free to the blind student. The school also offers graduates a lifetime of support with an alumni association, in-home follow-up visits, and they even reimburse many veterinary costs, including those of retired guides. I can see why Oriano was impressed. There is a lot of support here.

Oriano’s first three guide dogs worked until they were 12 or 13 years old. That is the best one can ask for. They were healthy and able to. Oriano was very good with his dogs–kept them exercised and did his best to keep them from forming bad habits that could cause guiding problems and potentially shorten their working lifespan. Of course, luck is a major factor too.

It is interesting to note how different each of Oriano’s guide dogs have been. Each a very different personality, yet each doing the same job.

Blazer, a stocky black lab, was Oriano’s first guide dog. Blazer worked hard guiding this young, on-the-go guy through high school and through four-years of a university economics degree. When I met Blazer in the spring of 1988, he already had a grey chin and was retiring with Oriano’s family.

A few months later, I watched Oriano get his second guide dog, Patton, in a ceremony under the San Rafael summer sun–the same day we got engaged. Patton was a smaller black lab with soft fur. My nickname for him was “ni ni”. Patton had a sweet, gentle, sensitive nature. He was the first guide dog I really knew. He guided Oriano to his downtown computer business daily for several years in the beginning of our new life together. He worked with Oriano through the renovation of our first house and later our first house-building stint. Patton guided Oriano fast and so strongly that when I was with them I’d have to semi-run to keep up. Often Patton’s forelegs were up off the ground–feet in the air like one of Santa’s reindeer. He retired with a grey chin like Blazer and became our pet. One of his favourite places to lie in our backyard during retirement was under our picnic table, as though it were his big dog house. At 16, Patton was euthanized on our living room floor. Although he was old and sick, he was still munching Milk Bones from my hand right up until his final moment.

Oriano got his third guide dog, Hillie, in 1998. She was his first yellow lab and first female. I still remember sitting on our living room couch and seeing her face turn to look at me as she stepped in our front door for the first time. Hillie was quite independent, smart and happy-go-lucky right from the start. It didn’t seem to matter who she was with, she was always content. And she had no concern for playing rough, sometimes crashing into Patton. Hillie’s walking style was the opposite of Patton’s. Hillie guided Oriano with a saunter, like she were on a leisurely Sunday stroll–no matter what day of the week it was. Oriano would usually be a step ahead of her, almost guiding her, which wasn’t ideal. Hillie had skin allergies early on that the vet couldn’t clear with medicine or diet. But as soon as Oriano put a water filter on the tap and she started drinking filtered water, bingo, we won. We assumed the problem must have been chlorine. Young Hillie travelled with us to Vienna. We have a photograph with her standing next to Oriano on the steps of Vienna’s historic pillared parliament building. Hillie also guided Oriano through two more of our house-building projects. She retired and became our pet for a few years. Then she suddenly turned sick with liver failure and died two days later on a pillow on the floor of the veterinary hospital with us stroking and holding her paws. She was 15 and a half.

Saying goodbye is always with tears, our hearts bursting with the fullness of love and memories, our home exuding emptiness, missing a family member.

After Hillie and before Birch, Oriano decided to spend six years walking with a white cane so he could polish his rusty white cane skills. For a blind person, both a white cane and a guide dog are equally valid choices for getting around. A white cane is the basic essential tool of travel for a blind person and good mobility skills with it are beneficial even if you usually walk with a guide dog.

No matter how competent a cane traveller is, you make your way in the world by making contact with it. Travelling with a white cane can’t be done without touching the ground and the things around you. If you want to discover what’s in your immediate environment, a white cane is what you need. With it you can explore by feeling. But you can’t expect to walk in a straight path with a white cane as you would with a guide dog. A guide dog can take you quickly from A to B, then to C, missing the obstacles.

Oriano’s white cane skills became golden. He would take the bus to town and tap his way to the post office, the bank, or to meet a friend for coffee, no problem. He is the best white cane traveller I know. The only thing he complained about was all the darn clutter littering the sidewalks and bus stops.

On his first trip into town after returning home from California with Birch, he remarked about it, “It’s like the sidewalks are suddenly clutter-free–clear of the poles, garbage cans, sandwich boards, chairs–all those irritating things that used to get in my way with the white cane. Now it’s smooth sailing.” It was as though he rediscovered what walking with a guide dog was like.

Guide dogs are trained to make decisions. If there is a bicycle left on a sidewalk, the dog has been trained to decide how best to go around the obstacle to continue on a straight path again. The dog and blind handler are a team and constantly communicate with each other. This is why it’s important to not distract a guide dog when it’s in harness and working. Distractions can be dangerous, a blind person’s life could be at risk. A blind person counts on their dog to guide them safely–to stop at curbs and staircases, to listen to the handler and do its job. The team is concentrating on what they are doing.

The relationship between the handler and the guide dog is like the relationship between a conductor and a musician. The handler, the conductor, informs the guide dog, the musician, on how to perform. Both have their separate jobs to do, neither more important than the other and they work together simultaneously towards a greater goal. Teamwork towards the goal of making music. Teamwork towards the goal of independent travel.

There are many ways a person can go blind. Some people are born blind. Some have degenerative eye disorders, diabetes, glaucoma, illness or suffer an accident, like Oriano did. As long as you are legally blind you can choose to use a guide dog. You might be fully blind or you might have some residual dregs of vision.

There is a long history of blind people being guided by dogs. Oriano told me it dated back to at least the days of Pompeii, so I Googled this interesting bit of information. I learned that a 79 AD mural uncovered near Pompeii in Herculaneum, a Roman seaside town that was covered in 75 feet of Vesuvius’ lava, clearly depicts a blind man being guided by a dog. Also, from the middle ages, a wooden plaque shows a dog leading a blind man with a leash. And a mid-16th century popular alphabet verse goes, “A was an archer…B was a blind man, led by a dog.”

The idea of the modern guide dog began in Germany when blinded soldiers returned from World War I. In 1927, Dorothy Harrison Eustis, a wealthy American guide dog pioneer in Switzerland, launched the guide dog movement internationally. She trained Buddy for a blind American man, Morris Frank, and this is thought to be America’s first guide dog. In 1929, Eustis and Frank co-founded the first U.S. guide dog school, The Seeing Eye. Guide Dogs for the Blind came later in 1942.

There are now four small guide dog schools in Canada and 16 schools in the U.S., four of which are large organizations like Guide Dogs for the Blind. The most common breeds used as guide dogs, because of their temperament, are black and yellow labs, golden retrievers, and less frequently standard poodles and German shepherds. Oriano and Birch are one of 10,000 guide dog teams in North America.

Before Birch, during Oriano’s hiatus from having a guide dog, the house at first felt empty. His guide dogs had been a part of our life together for over 20 years. But then I noticed a sort-of relaxation–early morning risings and daytime feeding/relieving schedules did not dictate our life like they had. Our life had been planned around the guide dog. When you have a guide dog, you live a guide dog lifestyle. Oriano and I also got to walk together arm-in-arm which we didn’t do much before. And I could choose to be lazier about vacuuming. But now that we are back in guide-dog-lifestyle mode with Birch–our wingless angel–life is great.

Our dogs have always been a source of pure happiness. The kind of happiness that splashes smiles across our face and jumps joy in our heart. A happiness that doesn’t mind the wet lick of a dog’s tongue. A happiness that stretches out coaxing, stroking hands even if the dog isn’t near. A happiness that effortlessly voices kind words and childlike sounds. A happiness that wants to evoke happiness–to keep the tail wagging.

***

They come to another corner and she stops at the curb. With the new lottery reward system he has started, of only sometimes giving her treats, she may or may not get a kibble this time. Her weight needs to be maintained. He feels the curb with his feet to make sure their position is correct and he listens to the traffic flow. She waits for his command. She does not read the green, yellow or red traffic lights for him. The traffic is now moving at their side, parallel to them. He may hear people crossing. He tells her that it’s okay to go forward. They cross the street in a straight line to the opposite curb and continue on their way.

Running Blind

“What is 900 kilometres long, two feet wide and can make a grown woman cry?” Immediately, Rhonda Marie Parke answers the riddle herself while chuckling, “Oh yeah, the Bruce Trail.”And who should know better than someone who has run the Bruce [southern Ontario] from one end to the other?

It seems that Rhonda Marie is no stranger to racing even though born with day blindness, a rare eye disorder leaving her with only 8 percent sight. Although she can see a little in the dark, she sees only shapes and blobs in the light, which explains why she ordinarily runs at night and the reason for the white blaze on the tree at the front of her house.

I am amazed at her taking on such a gruelling run, one that even few with full sight would attempt.

“How did you accomplish such a feat?” I ask her.

“When I first started running seriously, I connected with Achilles Canada, who matched me with guide runners who taught me how to run safely and overcome my fear of running blind,” she explains. “The terrain is rugged as it runs along the Niagara Escarpment, making it easy to twist an ankle, and there are other factors to consider, such as 100-metre drops, climbing the numerous stiles (120 of them) and watching out for wildlife like bears and rattlesnakes,” she continues.

I recoil a little at the mention of snakes but encourage her to go on.

“I needed two guides per day to cover the 20-day run, and it was their job to warn me of upcoming obstacles. When it got boring, we made up some colourful language to describe the various barriers along the way. Mashed potatoes meant there was a muddy section ahead, mounds of opportunity if there was an incline. I can still hear the guides calling, ‘Ankle grabber coming up on your right,’ or ‘Chicken head straight ahead,’ warning me there was a root sticking up in the path. My favourite one to hear was Butterscotch pudding, meaning that finally, we were approaching a part of the trail which was smooth enough to run. However, I didn’t want to hear Death to the left, as I knew a dangerous drop lay ahead.”

“That’s quite an interesting way to break the boredom navigating your way along an unfamiliar trail like the Bruce,” I comment but cringe at the warning Death to the left.

“Also, as I didn’t know most of my guides before the run, sometimes I asked them to talk about their running experiences as they guided me. Often they were nervous about doing so, but I convinced them that I could tell if the ground was rocky or covered with roots by the echo of their voices. So they would agree but would still call out warnings as needed.”

“And you made it the whole way,” I say incredulously.

“Yes, despite cold, wet weather, lack of sleep, blisters, and a sprained ankle, my guides and I reached the stone cairn marking the most southerly point of the Bruce Trail August 23, 2014, at 1:30 p.m. As I jogged toward the final destination, close to Queenston Heights, a group of well-wishers including some with physical challenges along with supportive friends, my team of guides, and my three children were there to cheer me over the finish line. Some even joined me for the final lap.”

“You must have been so proud, not to mention exhausted,” I say, emotionally spent just hearing the story.

“Well, I certainly was exhausted,” she agrees, “but it was a big accomplishment.”

“So why do you do it?’ I have to ask.

“I do it to make other-abled Canadian runners aware of Achilles. I also want to change the way the world thinks about disability. We want the world to know that we are out there,” she says. “And we are trying hard. We want the chance to try and fail.”

To Rhonda Marie, disability means many things. But using it as an excuse is not one of them. She encourages those who are other-abled to see their difference as a limitation, not necessarily a dead end. She believes that once you make peace with your difference, with the help of developing strategies, you can succeed no matter who you are. Still, she understands that it’s not easy to accept a disability. “It’s a crappy road full of roots and rocks. It’s tougher than the Bruce.”

Yet this did not stop her. She has run other trails and ultramarathons, one being the Barkley Marathon in Tennessee, considered the most brutal. Although most do not finish the gruelling 100 miles, 160 kilometre race in the required 60 hours, runners return every year to compete. Rhonda Marie was the first blind athlete to attempt this event. Rhonda Marie also ran the Boston Marathon in 2013, the year of the bombing. She recalled the chaos in one of her posts: “I remember the crying, the shock and the fear. I remember holding my kids so tight. I remember running the next year.”

In 2018 she ran across Tennessee as part of the Last Annual VOL State Race to raise funds for Achilles Canada, advocacy being one of her main reasons for running. This race was 314 miles long and had to be completed in 10 days. She did this without a guide. When asked why, she said she wanted to illustrate the struggle of differently-abled people. Even though this race is impossible for most people, this is why she loved it. “It’s like every day for a visually impaired person. We have to deal with being scared every day.”

This race was especially perilous for a blind runner as a lot of it took place on roads and highways. Since pacers were not allowed, her friend Chris drove by every four hours to check on her. Also, some of her guide friends created an app that reminded her of identifying landmarks, curves in the road, etc. Thank goodness for the VOL Angels as there were no water stations along the way.

Of 117 runners that started the race, 83 finished. Rhonda Marie was the 64th to reach the finish line, also known as “the Rock”. A photo of her running alone in the dark with only a headlamp and white cane visible is an example of her tenacity. She completed the race in eight days, 16 hours and 25 minutes. However, she ran /walked the last 100 miles on two stress fractures in her right ankle, later requiring surgery.

“Thankfully, I had my family and friends to support me over those tough months as well as my cats to entertain me,” Rhonda Marie remarks cuddling one of her many feline friends. “And I did a lot of crocheting, knitting, cooking and reading to help me make it through those long hours of waiting.”

Rhonda Marie is also a registered massage therapist. Ironically, she started running seriously at the same time she started her business. Fortunately, having her practice booked solid months in advance has also helped her through this time of loss.

“All these things keep me busy and distracted. I try hard not to love running, as trail running is no longer possible. Now I’m limited to running five kilometres, a maximum of two or three times a week, because of osteoarthritis and the lack of cartilage in my ankle. It’s been life-changing, something I still struggle with today. Losing running has been like losing my best friend, and there is grief with that loss.”

Still, Rhonda Marie says, “Everyone should be given the right to chase their finish line, but for that to happen, one has to have the right to stand at the start.”

Rhonda Marie is running again because of a great deal of hard work and determination. When her ankle healed, she started training. The first step was to walk unaided. Then she began first walking, then running on the treadmill. It took two years before she was comfortable running again. Whether hiking, snowshoeing, golfing or running, this petite, 46-year-old does it all, accompanied, of course, by friends or family, as her sight in the daytime is minimal. Simply put, Rhonda Marie is an inspiration to everyone!

In her latest email to me, she closes with a P.S. which reads, “Just going out for a run.” She sent the email at 4:04 a.m., the hour she jokingly refers to as ‘stupid o’clock.’ Because Rhonda Marie runs in the dark, she is nicknamed ‘Batgirl’ by her running friends. But ‘Batgirl’ must arrive back before the light of dawn, or she will no longer be able to see the white blaze which calls her home after a run in the dark.

Footnote: In reference to the name – The Last Annual VOL State Race, the Last Annual part is an inside joke as it never turns out to actually be the last race as more runners keep coming back each year. The VOL part is because Tennessee is called the state of volunteers. An example of their volunteerism is the Vol Angels who, along the race route, left water, food and sometimes the offering of a place to rest for the weary racers.

Sewing

I found this article informative and inspiring as I once was an accomplished sewer, having made dresses, blouses, skirts, jackets, a trench coat – clothes for my mother, sister and myself. I also taught both my brother and sister to use the sewing machine. It was a hobby I loved. But now that I’ve lost most of my vision, I have felt that I cannot do it easily anymore, that I can hardly sew a fallen button back on.

This article has helped me realize that sewing can still be possible. An article like this is a good reminder that we do not need to be limited in our abilities, if we really want to do the thing.

The Braille Monitor editor’s note (excerpted): Ramona Walhof grew up in a small farming community in rural Iowa. She, her brother and sister were born blind. Yearning for something to do during one long, dull summer, Ramona asked her mother (who was an accomplished seamstress) to teach her to sew. The story that follows is her account of a lifetime of satisfaction and practical good—from hobby, to employment, to family budget-stretcher—gained from this rapidly disappearing art.

Along the way, Ramona (who was widowed in her early 20’s) also raised two children, owned and managed a commercial bakery, taught school, [and ran several other businesses].

When I learned to sew, I never thought much about blindness. I didn’t avoid thinking about blindness. It was a part of me. But when I needed a method to do something that others did visually, I just did what seemed most likely to work. Nobody suggested that blindness should prevent sewing until I knew better.

As I grew older, I came across blind girls and women who had been actively discouraged from doing things I learned as a child. Sewing for me has provided employment, relaxation, challenge, and accomplishment. It has helped me to learn about fabrics, styles, and colors. There are things I never attempted (some because of blindness) but most because of lack of time. Perhaps one day I may still take up some new kinds of sewing such as quilting. I know it would be delightful to do if I ever get to it.

When I was a young child, summers were boring. My brother, sister, and I attended the School for the Blind during the school year. We were very glad to go home at the end of May each spring, but we didn’t have a lot of friends in our home town, and we got tired of not having enough to do. We took swimming lessons, participated in local church activities, helped with cleaning and cooking (washing dishes was the worst), visited with grandparents and cousins. We hauled as many Braille books home from school as we could fit in the car with all our clothes and other possessions. My brother managed to talk our Dad into some ham radio equipment and entertained himself with that. My sister and I generally rationed our books some and got Braille magazines, but there never was really enough to do.

One summer, (the one after my fifth grade year), I decided to try to solve the problem. I announced to my mother with the diplomacy customary for me at the time, “This summer you are going to teach me to sew.” My mother had been making clothes for us as long as I could remember. We got some school clothes from stores and from catalogs, but the ones she made were always nice, and we could help decide what they would look like. Several people in our family sew, and my mother had a buttonholer on her machine, so people would bring their garments to our house to do the buttonholes. So it seemed natural for me to want to sew.

My mother didn’t resist at all. She responded with a question, “What do you want to make?” I never asked her what she thought about it, but I really don’t think she was shocked. Perhaps a little uncertain about some of the techniques. Actually, techniques were not a problem. I told her I wanted to make gym clothes. I figured a few mistakes could be tolerated in gym clothes. I think that neither my mother nor I knew that blindness was much of a factor, so it wasn’t.

We decided that the gym shirt should have a plain round neckline with cap sleeves. This was my idea so that I would not have to gather the sleeves and set them in. My mother cut a pattern out of newspaper, designing it from something else she had. I pinned the pattern on the material and cut it out. Then my mother realized that she had forgotten the cap sleeves, so they had to be set in after all. This made the project more complicated for a beginner, but the gym shirt looked great to me. I learned to guide the material through the sewing machine using a quilting guide my mother had. I learned to pin seams and hems closely and remove the pins just before they came to the presser foot. I learned to move the gathers on the gathering thread and put them where they should be when I pinned the gathered piece to the one it needed to be sewed to. Really, it wasn’t as hard as I had feared. I wore that gym shirt all through sixth grade. I don’t think we ever got to the shorts.

Marking darts could be done with pins or basting threads. There were so many different kinds of darts that it took me some practice to get them all figured out. Gradually, I got so I could judge the size of darts pretty accurately without having to use the marks from the pattern itself.

When we came home for Christmas that year, I made a yellow skirt. It turned out all right, too. This time I used the tissue paper pattern. My cutting technique seemed obvious to me, and my mother never commented on it. Only later did we learn that blind people weren’t supposed to be able to cut around tissue paper patterns.

I held the scissors with my right hand the way most people do. I looped my left hand over the top of the scissors with the thumb and fingers opposite each other right at the part of the scissors that did the cutting. If the edge of the pattern was at the top of the bottom scissors blade, I could feel tissue paper on one side and fabric on the other. If the scissors were not right at the edge of the pattern, I would have paper or fabric on both sides of the bottom blade. The more practice I got, the better I got, but even as a beginner, I could cut reasonably well along the edge of the pattern.

Patterns come in an envelope in big sheets, and my mother would cut the pieces apart and trim on the cutting lines. She never really read the instructions to me. Rather, she taught me basic concepts about how to set in sleeves, turn down a skirt band over the seam, set in a zipper, assemble and attach a collar, etc. She also taught me to identify pieces of garments by their shapes. Sleeves would tend to be round at one end and square at the other. Blouses and dress tops had big arcs cut out where the sleeves would be attached. The curves at the front and back of slacks and shorts were shaped differently from sleeve curves. The curve at the back was bigger than the curve at the front for slacks patterns, but the curve in the front of the top where sleeves are in-set is bigger than the one at the back.

Much later I learned that the instructions printed with the patterns could often be helpful when taking on a new style of garment. I am sure my mother read the instructions, because she often used them when we were laying out fabric before we cut it out. But we often found better ways to make efficient use of the material than the patterns showed. I don’t remember what I made during the summer after my sixth grade year, but I am sure there was something.

In any case when I enrolled in home economics in seventh grade, I already knew some of the basics about sewing. Our teacher was new that year and had no background working with blind girls. Our first project was to make an apron. There was no cutting. Everything was on a straight line and could be torn with the grain of the fabric. The aprons had a blue border at the bottom with a flowered print above. The bands and sashes were straight pieces. The sashes had to be hemmed, and aprons had to be gathered and attached to the bands.

There were eight girls in my class, and most of us could sew a hem fairly straight by the time the aprons were done. The teacher really didn’t want us to run a machine without having her present to watch. I disregarded this instruction without too much teacher protest.

I learned about the seam guide in that class. You can buy a little metal hump that screws into the top of the machine cabinet which is better than my mother’s quilting guide. For the rest of the first semester our home economics class cooked. Second semester was the real sewing class. My friend and I decided to make tangerine skirts, but they were different patterns.

The teacher’s first notion was that she would cut out all the patterns. Unfortunately for her, I was there to object. So I cut out my own pattern. I also offered to help other kids learn to do it. Some of the girls really didn’t have much trouble. Some tended to place the fingers of their guiding hand at the end of the scissors instead of where the cutting occurred. They were constantly being warned to be careful not to cut themselves. Since I thought everybody knew better than to close the scissors with fingers between the blades, these warnings seemed unnecessary. Certainly, some of the students were more fearful of scissors than they needed to be. We also learned how to assemble all our different patterns.

When I cut out my blouse, I made an error. I should have laid the back on the fold, but I cut it on the edge of the fabric, thus requiring a seam where there should have been none. If I had not been so determined to do it myself, the teacher doubtless would have found this error before it was done. Some students were much too cooperative in my judgment and did not do as much of the work themselves as they could and should have.

We could all thread a regular needle using a needle threader with a fine wire loop. When the wire loop is in the eye of the needle, the thread is brought through the loop. When the needle threader is removed from the needle the thread passes through the eye. Large eye needles made this easy. Our teacher encouraged basting, but most of us didn’t like to do it. We all learned to baste, though, because we were required to baste zippers. We also learned to hem garments with an overcast stitch. It was desirable not to see the thread on the outside of the hem. With practice, some of us got pretty good at this.

Threading the machines presented another challenge. When threading the machine, one needed to pass the thread through several metal or plastic loops. No one had trouble learning where to put the thread, but we would not notice loops of thread that got caught in other places while we were doing the threading.

It took me a while, but I finally realized that if I kept the thread taut from spool to needle while doing the threading, I could tell if there were errors or loops where they should not be. We always blamed the tension if something went wrong, and I feel sure that we did inadvertently turn the dial at the tension sometimes.

With experience, I learned to tell from the stitching itself when the top and bobbin tensions were balanced. My mother was casual about making constructive suggestions about things like this and more helpful than anyone else before or since. She would tell me what she looked for, and I could try to learn the same information by touch. More often than not it worked. Everyone (including me) tended to rely on somebody’s eyesight for certain judgments at first. If a sighted person wasn’t conveniently available to help when wanted, this became a nuisance and provided motivation for all of us to develop techniques that a blind person could use independently.

It is surprising for me now to think about how difficult it sometimes seemed to feel proper stitching. If we had expected to be able to do it from the beginning, we all would have found it easier. As it was, this took some time and experience.

I continued to make clothes during vacations and in home economics. I enjoyed the making and the wearing of the clothes. I also enjoyed making things for others, but seldom had enough confidence to do it. I made a shirt for my dad and a baby dress for a cousin, and I think they were OK.

During college I did not have access to a sewing machine and did very little sewing. Shortly after I was married, though, a sewing machine seemed important to have. We bought a cheap one, a portable one that weighed a ton. It was very heavy to lift on and off the dining room table, so it stayed at one end while we ate at the other during many weeks. I usually put it away on weekends.

I took a set of big bath towels that had been wedding presents but were not being used and made my husband a bathrobe. He was pleased and wore it a lot which pleased me. We still have a picture of him sleeping in a recliner in that bathrobe with our first baby on his shoulder also asleep. When I got pregnant, I knew I could save money by making maternity clothes. I did make some, and my mother made me some, too. We didn’t spend much. Then, of course, it is even more fun to sew for your children.

Knits were the big thing in the early 70’s so I took a short course at the YMCA in stretch and sew. We didn’t sew during class. We took our assignments home, so the teacher had no occasion to worry about blindness. If she didn’t explain something, I asked, but this was easy for all. I made pants and a shirt for my daughter who was a toddler and a matching set for my son who was a tiny baby. I also made a shirt for myself. I offered to make my husband a shirt, but it never got done. It was already cheaper to buy t-shirts than to make them.

After my husband died and I returned to work at the Commission for the Blind in Iowa, I was immediately assigned to teach sewing along with Braille. My students all wanted to sew with knits, so the stretch and sew class was far more valuable than I had ever dreamed. Some of my students were beginners, and some had far more sewing experience than I. This concerned me at first, but I found that we could learn from each other in wonderful ways.

Several of my students went home and took up sewing a lot. Others did less but enjoyed it. One young woman had been a professional seamstress in an alterations department for a big store. She chose to make a jacket that had three parallel rows of top stitching for trim that were supposed to be done in three different colors. I cautioned her about this, but that is the kind of thing she liked. I thought that her control as a newly blinded seamstress might not be as good as desirable for something that showy, but it really turned out fine. I cannot say how many students I taught sewing or how many outfits I made for myself and my children during the next several years, but I gained a lot of experience.

It was during that time that people began using machines with cams and other kinds of fancy stitches. These made sewing even more fun! Making decorative items or decorations on clothes was something we had to do. We just couldn’t ignore these interesting new sewing machine features.

When my daughter was in second grade, she joined Bluebirds. They were supposed to make red felt vests, and none of the mothers wanted to take on this project. I thought felt vests were not sensible for second graders. One slip of the scissors would be ugly, and felt was expensive. I offered to have the group make skirts at my house. Other mothers thought I was crazy, but agreed. It was simple—use navy blue rectangular pieces of polyester knit fabric. Turn down the top enough to pull three-quarter inch elastic through. Turn up the bottom two inches and sew red rickrack around at the top of the hem. There was only one seam required and no hand sewing. The girls could use the sewing machines if their mothers would let them. The skirts were cute as they could be, and the girls were proud as peacocks.

By the time my daughter was in sixth grade, it was clear to me that she wanted more clothes than I was willing to buy. I told her she could probably have more clothes throughout junior high and high school if she would learn to sew. She was more than eager. She chose to make a three-tiered white skirt with purple trim. The gathers on three tiers wore her out, so I helped, but she did the rest. She wore it for her sixth grade graduation and looked great. When she was called to the front for the top award from the school, I had tears and wished one more time that my husband could have been there to share it with us.

Anyway, Laura was a confirmed sewer, although she still had a lot to learn. We began to learn about new kinds of patterns together. While she was in high school, she made casual clothes, but I did the more formal ones. When kids need something for school, you don’t always get much notice. When Laura joined the orchestra, she needed a black formal. Her friend’s mother knew the right pattern, and I made it. For her first formal dance, I made her a mint green long satin dress with puffed sleeves and an inverted “v” below the bust. She had a good bustline, and the dress looked good on her. She took it to college with her, when the time came.

Now, Laura does more sewing than I do. She got practice during college and made a friend’s wedding dress. Today, for me sewing is a hobby, but it is there when needed or wanted.

I love to share this experience with others. It is a way of being creative and busy. One summer I went looking for clothes and just couldn’t find much. Before long I switched to shopping in fabric stores and had the clothes I liked. Making a work dress can be done in about the time needed for two shopping trips, and if shopping isn’t going well, sewing is more satisfying. I also can make clothes fit the way I want them to. If I ever have grandchildren, there will probably be things to do for them. Time will tell.

If I ever have an opportunity to teach sewing again, I will be much more confident about what projects my students should attempt. One more thing: For a blind person who likes to read recorded books and magazines, sewing is one of those things you can do while reading.

Blind Canadian Paralympian kicked off Virgin cruise receives free ride

Former Canadian Paralympian Donovan Tildesley was kicked off a Virgin cruise ship in Miami because he is blind and was travelling solo.

(Virgin Voyages)

November 14, 2022

Reprinted from CityNews Vancouver

A blind Canadian Paralympian who was asked to get off a Virgin cruise ship in Miami because he was travelling solo has received an apology and a free ride.

Donovan Tildesley says shortly after he boarded the Valiant Lady, he was approached by two of the ship’s personnel and told it was unsafe for him to be on that particular cruise as a blind person.

Donovan Tildesley on Facebook:

I boarded the Valiant Lady, one of the newest ships from Virgin Voyages just after 3 o’clock this afternoon. While finishing my second drink at the patio bar just after 5:30, two of the ship’s personnel informed me that it had been decided that, because I was travelling solo, the legal department at Virgin had deemed it unsafe for me to travel on this particular cruise as a blind person. Apparently they didn’t have the supports in place for my safety. I have travelled the world, taken three other cruises, one of them as a solo traveler, but this has never happened to me before! You would think a big company like Virgin would have checks and balances in place for people with disabilities!

— feeling shocked in Miami, Florida