The Blind Canadian is the flagship publication of the Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB). It covers events and activities of the CFB, addresses issues we face as blind people, and highlights our members. The Blind Canadian:

- Offers a positive philosophy about blindness to both blind readers and the public at large

- Serves as a vehicle for advocacy and protection of human rights

- Addresses social concerns affecting the blind

- Discusses issues related to employment, education, legislation and rehabilitation

- Provides news about products and technology used by the blind

- Tells the stories of blind people

- Archives historical documents

The Blind Canadian is published twice annually and comes in print and on CFB’s website at www.cfb.ca in both web and pdf versions.

EDITOR: Elizabeth Lalonde

Canadian Federation of the Blind

Oriano Belusic, President

PO Box 8007

Victoria, BC, V8W 3R7

Phone: (250) 598-7154 Toll Free: 1-800-619-8789

Email: editor@cfb.ca or info@cfb.ca

Website: www.cfb.ca

Find us on Facebook

Twitter: @cfbdotca

YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/CFBdotCA

From the constitution of the Canadian Federation of the Blind:

The purposes of the society are:

(1) to provide positive public education about blindness in order to improve the social and employment opportunities of blind people;

(2) to create and maintain initiatives to improve the lives and the status of blind people;

(3) to encourage a model of service delivery in which blindness-specific programs empower and are accountable to blind people;

(4) to support legislation that protects the rights of blind people, and to provide support and advocacy in cases of discrimination against the blind;

(5) to provide Federation settings in which blind children, youth and adults have access to mentoring with successful blind role models;

(6) to act as a community resource for knowledge and positive attitudes about blindness for the benefit of teachers and parents of blind children and youth in order to enhance their social and educational opportunities;

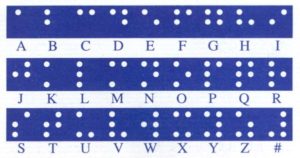

(7) to increase self-confidence, travel skills, Braille literacy and independence in blind people;

(8) to provide opportunities for blind people to meet for support, networking and self-improvement;

(9) to promote the following statements of principle:

–(a) We are not an Organization speaking on behalf of blind people; rather we are an Organization of blind people speaking for ourselves;

–(b) We believe that with training and opportunity, blindness can be reduced to the level of a nuisance;

–(c) We believe that blindness is not a handicap, but a characteristic;

–(d) We believe it is respectable to be blind;

–(e) We believe that blind people can compete on terms of equality with their sighted peers;

–(f) We believe the real problem of blindness is not the lack of eyesight, the real problem is the lack of positive information about blindness and the achievements of blind people.

The Blind Canadian is published by the Canadian Federation of the Blind

(c) Canadian Federation of the Blind 2002

Please send all submissions and letters to the editor:

E-mail: editor@cfb.ca

Fax: (250) 595-4849

The Blind Canadian

1614 Denman Street

Victoria BC (Canada)

V8R 1Y1

FROM THE EDITOR

This, our first issue of The Blind Canadian, celebrates the Canadian Federation of the Blind, a group of blind Canadians working with passion and determination to create a positive and independent future for blind people in this country.

This publication portrays the philosophies, beliefs and goals of members of the Canadian Federation of the Blind and serves as a source of positive information about blind people and our strategies for success. Articles are written from the perspective of blind and sighted people who understand that blindness is not a handicap but a characteristic. The words in these pages address the social and economic inequalities of blind people in Canada and celebrate the strides blind people are making to overcome these societal barriers.

Our goal in this publication and in our federation is to create new, positive attitudes about blindness and change what it means to be blind.

I am looking forward to sharing new ideas and approaches with you. I encourage everyone to submit articles, essays, stories, poems and other pieces. I invite you to write letters to the editor, expressing your views on subjects discussed in this publication. Dialogue and debate are essential to the success of a publication and an organization.

It is time for blind people in this country to explore traditionally-held beliefs about blindness. It is time to sort out these old ideas, keep what is valuable and discard what is holding us back. It is time to begin forging a newer, freer, more positive view of ourselves, what we can do and what others expect of us. Join us as we work to create a better future for blind people in Canada.

Elizabeth Lalonde, Editor

Celebrating Blindness

BY ELIZABETH LALONDE

Our members have discussed the idea of celebrating blindness, and in this essay I will explore the topic in more detail.

The notion of celebrating blindness is foreign to most people. Usually, when we think of celebrating, we think of parades, parties and rituals. But this is not what I mean by celebrating. I am talking about something simpler, about pride, pride in oneself, as reflected in the statement, “I am proud to be blind.”

Some blind people are more comfortable than others saying they are proud of the achievements of blind people. I am proud of the achievements of blind people, but I am also proud to be blind.

Regarding the topic of pride, I don’t necessarily mean pride in the biology of blindness, I mean pride in the heritage, history and achievements of blind people. Saying I am proud to be blind encompasses these things and more.

For example, many First Nations people say they are proud to be First Nations. What are they actually saying? Are they saying they are proud of the biological fact of being native, or that they are proud of their heritage, cultural traditions and accomplishments? We don’t have to ally our movement to other social movements, but we can learn from other oppressed peoples and gain useful insights about how they progressed.

It is hard to build a movement unless the people in the movement take pride in what makes them a movement, whether this is gender, sexual orientation, cultural background or blindness. The example of Deaf people best illustrates my point, because it exemplifies a group of people who also lack one sense.

The Deaf movement is working hard to improve the lives of deaf people in society. Of course, deaf people have their own language and culture, which makes their situation different from ours. But, we can learn from their example.

Some Deaf people who associate themselves with Deaf culture spell the word deaf with a capital D. This capital D distinguishes them from those who spell deaf with a small d. The capital D signifies the person associates with deaf culture and that they take pride in their deafness. Here is a piece written by Dr. Frank Lala that explains a common way of thinking among Deaf people.

A CREDO FOR DEAF AMERICANS

BY DR. FRANK LALA

We don’t choose to be the common silent minority

It is our right to be the uncommon and noble silent minority

If we can, we seek opportunity, not security

We don’t wish to be “kept” citizens, humbled and dulled by having the state look after us

We want to take the calculated risk…. to dream and to build, to fail and to succeed

We want to abolish stereotyping, and to remove the prevalent public mentality toward prejudice

We will not tolerate biased perceptions, criticisms or censures of our beloved American Sign Language

We will not accept abuse of our Deaf identity by oppressors, nor our rights to self-determination

We refuse to barter incentive for a dole

We prefer the challenge of life to a quarantined existence; the thrill of fulfillment to the stale calm of Utopia

We will not trade freedom for beneficence, nor our dignity for a handout

We will never cower before any master, or paternalistic attitudes, nor bend to any threat of discrimination

It is the heritage of our Deaf Culture to stand erect, proud, and unafraid;

to think and act for ourselves; to enjoy the benefits of our creations,

and to face the hearing world boldly and say, “This we have achieved.”

–DEAF AWARENESS HUNTSVILLE WEB PAGE

If that isn’t a declaration of pride, I don’t know what is. This is what I mean by saying I am proud to be blind. When we talk about whether to say we are proud of the achievements of blind people or proud to be blind, what are we really saying?

Would First Nations people spend one minute of their time discussing whether they are proud to be First Nations or proud of the achievements of First Nations people? What are we afraid of? Why do we hesitate to say we are proud to be blind? As blind people, we need to explore this question in greater depth.

Having said all this about blindness encompassing history, heritage and accomplishments, I cannot ignore the biological fact of being blind.

Most of us are proud of the history, heritage and achievements of blind people, but most blind people aren’t proud of the biological fact of blindness. But we can’t separate these two ideas. If we weren’t blind in the biological sense, the other qualities, our history, heritage and achievements, would be meaningless. If we weren’t blind in the biological sense, we would be sighted, and pride in our blindness would be irrelevant.

As for the biological fact of being blind, one could say there are things blind people do more efficiently than sighted people, such as finding our way in the dark, opening a lock without light, reading Braille with our fingers. But these are all things sighted people could do if they tried.

There is also the question of the blind experience. Do blind people perceive the world differently? Are blind people more perceptive? These are generalizations. Not all blind people are perceptive, and the blind experience is not significantly different from the sighted experience. So perhaps these are things we can’t be proud of, except on an individual level.

For myself, blindness has increased my perception. Because I have overcome obstacles in my life, I have a greater ability to empathize with other people who face challenges. I have my own idea of how blindness has affected me as a person, but this idea might be different from that of another blind person.

Perhaps I am shying away from saying there is a blind experience because if I admit there is a blind experience, it would be like saying I am different.

I want sighted people to know I am not different, that I can do the same things they can do. This is a dilemma. Do I deny the existence of a blind experience to prove I am like a sighted person, or is there a middle ground? Can I do the same things as sighted people, live in the same world, compete on an equal level, and still believe blind people sometimes perceive the world differently? This is another question to explore.

Our members have also discussed the idea of blindness as a neutral characteristic. Blindness is a characteristic, but I do not believe it is neutral. Blindness has affected my life in numerous ways. It has provided me with a range of experiences, encounters and feelings, some positive, some negative and some neutral, but blindness as a whole is not neutral.

Most characteristics aren’t neutral.

Being a woman is a characteristic, but it is not neutral. Being a woman means the ability to bare children. It also involves sociological and cultural factors, good and bad.

Being short is not neutral. Being short means I cannot reach high shelves. It also means I can crawl into small places. The characteristic of being short has at least two and probably more effects, positive, negative and neutral.

Perhaps if we removed the sociological and societal influences from certain characteristics, they would be close to neutral. But this would be a mistake. If everyone was the same, the human race would be one homogeneous mass, with no distinct cultures, values or beliefs.

Unfortunately, discrimination results from our differences, and this discrimination must stop. But, in the process of stopping discrimination, we don’t want to lose our distinctiveness. In fighting so hard to be successful in a sighted society, I do not want to lose my uniqueness.

This essay discusses many things. It touches on perception of blindness and on what it means to be blind, on celebrating blindness and on being proud to be blind. I am now exploring these topics and am interested in hearing your perspectives.

–Elizabeth Lalonde, Editor

U.S. National Federation of the Blind Convention

BY DORIS BELUSIC

For anyone unfamiliar with National Federation of the Blind conventions, they are life-changing experiences. I feel fortunate to have attended three of these conventions with my husband Oriano: Atlanta, 1999; Dallas, 1998; and New Orleans, 1997. Each time, we returned home full of inspiration and knowledge that became integral to our daily lives.

The convention is an annual, week-long gathering of thousands of blind people from around the world, of all ages and backgrounds. These people come together in a positive atmosphere to celebrate the personal and collective achievements of people who are blind. They come to learn, find inspiration, recharge and have a good time. Many are repeat convention-goers who have been attending for decades.

Around the same time each year, a large U.S. city hosts the convention. Federationists stay in a first-rate hotel, which offers excellent rates.

The convention boasts a jam-packed agenda, and there is something for everyone. There are seminars and workshops on topics such as computers and technology, jobs, Braille, and ham radio.

There are meetings for dog guide users, diabetics, parents of blind children and the deaf/blind. There are meetings of blind merchants, educators, lawyers, journalists, industrial workers, entrepreneurs, public employees, health care professionals and musicians. There are social events and activity tours for adults and families and a day camp for children.

The Exhibit Hall is a major attraction providing everything from Braille, print or tape publications on blindness issues, to aids and appliances useful to the blind.

Hundreds of salespeople demonstrate new technology and people browse, ask questions, and try the equipment.

The banquet is the highlight of the week. This event features good food, a chance to mingle with other conference-goers and a keynote address from the NFB president. The core of the convention is the three-and-a-half-day long General Meeting. This meeting consists of presentations, information, organization business and door prizes.

The convention sports a hubbub of activity. People meet old friends and make new ones. They share ideas and learn new skills. They do all this in a busy and stimulating environment, where blind people aren’t ashamed to use their white canes and guide dogs, where they are proud of their accomplishments.

The U.S. NFB Convention provides an important educational and inspirational experience. It represents the culmination of our philosophy. It is where we witness blind people at their best.

We learn blindness is a characteristic, not a handicap. We learn that with training and opportunity, blind people can compete on terms of equality with sighted peers.

We learn the problem of blindness is not the lack of eyesight, but the lack of positive information about blindness and the achievements of blind people.

We learn it is respectable to be blind. We learn to speak for ourselves. We see that the traditional concept of blindness is changing and we become free of old, negative attitudes.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

–Margaret Mead, Anthropologist

Blind Pride: MY JOURNEY

BY ELIZABETH LALONDE

My friend Heather and I are late for our first aerobics class. We rush in and hang up our coats. I lean my white cane against the wall and walk forward to join the class. Music plays loudly, a pounding, electronic beat. The teacher stands at the front of the room yelling instructions, but it’s hard to hear what she says. Heather and I warm up at the back of the room. Heather explains the movements to me, and I try to follow along. She speaks loudly, so I can hear over the music.

“Keep your shoulders still and kick your legs.”

I stand erect and lift my legs, angle them to the side and point my toes. But, Heather says I’m supposed to bend my knees. I try this movement, but Heather says the class started a new exercise. Now we have to lift our arms in the air, walk forward and then step back. The person in front of me prances back as I move ahead. We collide. I laugh and step out of the way. Finally, the class ends, the music stops. Everybody rushes to the change rooms.

I wait to talk to the instructor about the class and how I can best learn the exercises. A long time passes before she comes over to us. Her spandex pant legs slide together as she walks.

“That was very distracting,” she says. I can’t possibly teach with you both conducting your own class at the back of the room.”

I feel hot. Sweat runs down my forehead. The teacher continues, her voice sharp. “There were times when I got very frustrated.”

My stomach clenches. I can’t control my anger, but I don’t say anything.

I just think, ‘You are frustrated? Do you know what it’s like for me to have the music so high that I can’t hear a word you are saying? Frustrated!’

The instructor turns to Heather.

“Maybe she could stand at the front of the class. Then maybe she could follow my movements more easily.”

The word “she,” “she,” “she,” pounds in my head like an unchanging drum beat. I want to say, ‘Don’t call me she. I’m right here.’

I want to justify myself to her, tell her blindness hasn’t stopped me from doing anything, tell her I ski, swim, skate, go to school. But suddenly I’m tired, so tired. All I want to do is leave.

Later I lie in bed. The air in my room is cold. I pull the covers over my ears and think about what happened. I should go back to the class next week. I should fight, raise awareness, let the teacher know I won’t be defeated so easily. But I wanted the class to be relaxing, a retreat from the stress of school and even from the need to be an activist. Everyday I teach people that blindness isn’t something to be afraid of, that blindness does not render one incapable. This time I don’t want to teach anyone.

I want to lean into the music, bend my back, twist my hips, point my toes and forget everyone around me. I would love to change the instructor’s way of thinking, go to aerobics class every week and witness the transformation, exercise on the last day of class and then listen as she tells me how much she’s learned from knowing me.

But I’m tired, and the image fades, and I know I won’t see her again.

I’m six years old. It’s reading aloud time. I’m sitting in a circle with the other kids in my class, a book pressed close to my face. My stomach sickens as the others read. Now it’s my turn. Slowly, one letter at a time, I speak the words. My face burns. I feel everyone watching me.

I didn’t learn Braille in elementary school.

The first teacher for the blind I had in Kindergarten thought I had enough sight to read print, but she forgot I would grow older, print would get smaller and books would get longer. Now I curse the inadequacy of an educational system that didn’t teach me to read in a system created for the sighted.

I started school a few years after blind children were integrated into regular classes. Integration, an upbeat word, a modern approach, a positive and necessary action, but what about its failures: the social isolation experienced by many blind children, the incompetence of teachers who don’t have the skills necessary to teach blind students. I’m torn by this dilemma.

I’m in PE class and the only child allowed to get six strikes in baseball. I stand feet apart, clutch the bat, take a deep breath, swing, slap air. Finally, I hit the ball. I run as fast as possible, but I miss first base and end up in the outfield before someone calls my name.

I didn’t want to be different. I wanted to play baseball as well as the other kids on my team. I didn’t know about ‘beep ball’, a baseball game with a ball that beeps and bases outfitted with buzzers. I didn’t know about ‘goal ball’, a sport with a ball filled with bells, tactile markings on the floor, and silence in the stadium except for the player who calls a teammate’s name just before throwing the ball.

Now I cringe at the stupidity of blind children competing with sighted children in a sport requiring vision. I was forced into a position where I was the worst player, the first one out, the last one across the finish line. How can a blind child gain confidence in a system that doesn’t allow the child to achieve his or her potential?

I’m in grade five, using my first visual-Tec, a machine like a TV with a tray underneath for a book and a screen that magnifies the print. My teacher makes me sit by myself, turned away from the other kids, at a large desk at the front of the class.

I slide the tray back and forth and look at the big black letters rolling across the screen and my clumsy handwriting, large enough for everyone to see.

One of the kids just behind me laughs and asks in a loud whisper, “Why don’t you get glasses?” A warm feeling of embarrassment rushes up my body. Tears fill my eyes. I slide the tray back and forth and pretend not to hear.

I’m ten years old, standing with Bill, the orientation and mobility instructor, getting my first white cane. He measures my height and gives me a cane as high as my chest. He shows me how to make a guard in front of my body by moving the cane to the right as I step with my left foot and moving the cane to the left as I step with my right foot.

I didn’t want a cane. None of the other kids had a cane. I didn’t want to be different.

Bill said I should take it home and at least use it for crossing streets. The cane folded into four parts and fit into my bag where it stayed most of the time. Whenever I came to an intersection, I would pull it out, walk quickly to the other side of the road and stuff it back into my bag.

The cane was a symbol of my difference.

I didn’t think so then, but I was ashamed of my blindness. I was shy and quiet and didn’t want to be conspicuous. I’d never met any other kids my age who used a white cane, so why should I? I didn’t know then how empowering and liberating it could be to use a white cane, how it could turn traveling into an adventure and make me feel proud.

My best friend Susan and I go outside at recess. We run to the cement balls mounted onto poles, which zigzag the schoolyard. Everyday we jump over these balls, and today I feel strong, full of energy and ready to play the game. The rain just stopped and the yard is muddy. Susan starts to jump. She goes ahead of me until I can no longer see her.

I take off my jacket and role up my pants. I run towards the blurry shape of the first ball. Just as I take off, my foot catches in a hole on the ground and I tumble, face first into the mud. I am just about to get up, dust off my clothes and keep going, when Susan yells from somewhere, drawing attention to my fall. She runs over along with a crowd of other kids. They cluster around me, and talk all at the same time. One of the boys calls me ‘blindy’. Susan tells him to shut up. Then she helps me stand.

Miss Brown, the on-duty teacher, comes over. Miss Brown says I don’t see well enough to jump the balls and that I should be playing something less dangerous. Miss Brown takes me into the medical room. She cleans the scrape on my leg and the cut on my face, and covers each with a Band-Aid.

But Miss Brown doesn’t do anything to take away my humiliation.

I was ashamed of my blindness then. Now I’m ashamed that I ever felt shame.

I was convinced sight was superior to blindness. Well-meaning sighted people lived according to a model based on sight, which I could never emulate, though I tried. I’m angry at that little girl, my younger self who tucked away her cane, kept her mouth shut and pretended to see.

But is it my fault that I believed the dominant sighted ideology?

The Canadian Federation of the Blind, a grass roots organization created by blind people, says we must “change what it means to be blind,” fight to create a society where blind people are treated as equals, where people think of blindness as a characteristic rather than a tragedy. But how could I have known this philosophy as a child raised among sighted children and denied many of the blindness skills that should have been my right?

I’m in grade seven. I’m having trouble reading my science exam.

The teacher asks Adam, a boy in my class, to read me the test in the hall. My body shakes as I sit on the cold floor listening to Adam’s voice.

I spent a long time studying last night, but now I can’t concentrate. Adam is one of the smartest kids in the seventh grade. He probably knows all the answers. He’ll think I’m dumb. I try to hear the questions, but his words run into each other. The familiar warm feeling comes, then the tears.

Later that day, Rita, the teacher for the blind, comes to see me. She reads me the exam in a spare room down the hall. Her voice is clear and slow. I relax. I respond to each question carefully and dictate my answers for her to write. I get an A on the exam.

After that, I took all my tests orally. Rita got me a talking computer and ordered my textbooks on tape. She hired a woman named Catherine to be my assistant. My grades, which had always been average, rose and, in my second year of junior high school, I got on the honour role.

Pride grew in me, at first only in tiny bits, small, slow changes like carrying my cane folded in my hand and asking for help when I needed it. I started to accept and understand the dichotomy blind people face. I learned I could do everything others could do, but sometimes I had to do these things in a different way.

I’m in grade 10. Catherine and I are riding on a tandem bike as part of my adapted PE program. The wind in my face, the speed, the sense of openness around us makes me feel free. We ride along a busy street and through an intersection thick with the smell of exhaust fumes. Eventually, we turn onto a country road and breathe in the scent of pine and damp earth and listen to the twitter of birds in the trees.

Catherine also takes me swimming. She teaches me the breaststroke and the front crawl. I glide across the pool, the water cool on my skin, my body light.

I am 15. Sandra and I meet at a lunch arranged by the teachers for the blind.

Sandra lives in Vancouver and is also legally blind. She only sees straight ahead and I only see through the sides of my eyes. As we eat hamburgers and drink shakes, we laugh at what a great combination we make.

I can still remember our laughter, solid and real. We were two teenage girls, “normal” for the first time in our lives, no longer different, united in our shared experience.

Sandra and I were both learning Braille at the time, so we Brailled letters to each other every weekend for practice. When I got a letter, I spent a long time fingering the dots, reading and rereading each page. For the first time, I could read my own mail, and I wanted to make this new pleasure last as long as possible.

Sandra and I visited each other on holidays. I took the ferry to Vancouver, and she met me on the other side. We rode the bus all over the city and walked with our canes in front of us. Passers by dodged us on the sidewalks. Parents pulled their children out of the way. But we didn’t care. When I was with Sandra, my confidence grew, and I no longer felt alone.

I’m in a high school English class. A student is reading a poem out loud while everyone follows along in the text. I try to listen, but a ceiling fan whirs. Its low murmur muffles any other sound. I ask the person to speak up. She raises her voice for a moment and delivers one clear line from Sharon Olds, but then her voice sinks again into a soft mumble.

Now the instructor writes on the board teaching a lesson about metrics and feet. Her chalk scratches incessantly. I ask her to tell me what she is writing. She reads a line, but then forgets to read the next three.

I raise my hand again. She apologizes and says I will have to keep reminding her.

The next day she writes stanzas from different poems on the board and asks people to come up and mark in the iambs. When the teacher forgets to read the first stanza, I raise my hand to remind her. When she forgets to read the next stanza, I again put up my hand. For the next half an hour, the cycle continues. Occasionally she reads out loud, but then immersed in what the other students are doing, she forgets. My arm is like a machine rising and falling in mechanical synchronism.

I try to be patient. The teacher has a lot on her mind. She’s attempting to do everything at once, but my arm muscles ache, and my mind is muddled. Later the teacher offers to review the class with me. I cannot prevent a feeling of frustration. If she had read everything on the board, I would have learned the material without having to spend the extra time outside class.

The following week, the teacher holds a contest. She puts a list of riddles on the overhead projector and says the student who finishes first and gets the most right answers will win a prize. The class grows quiet except for the occasional cough and the sound of pencils scratching on paper. I sit still, speechless. My heart beats hard. Nobody seems to realize that I can’t participate. Even the students on either side of me sit hunched over their notebooks. I want to yell, splinter the silence, turn off the overhead projector and tell everyone to see how many questions they can get right. But I don’t say anything.

Finally, the teacher comes over and says she forgot me when she made the assignment. She starts to read some of the questions so I can type them onto my laptop, but before I can think of any answers, a student in the class says she’s finished. The contest is over. The teacher gives her a free pass to a poetry reading. The class laughs and calls her the master riddler. I don’t laugh.

How could they give someone a prize when I’ve been excluded from participating in the contest? Does anyone notice? Does anyone care? I get up and go to the washroom. As the cold water runs over my hands, I acknowledge a deep rage inside me, thick and indigestible.

It’s my last year of high school. Rita takes me to an interview with a rehabilitation counselor to get funding for a new talking computer and college tuition. I wear a blouse and skirt, tie my hair in a bun and walk with confidence into the office.

My interviewer’s name is Mr. Clark. Mr. Clark has a pinched voice. He coughs nervously as he asks me questions about my grades and where I want to go to school. He fiddles with objects on his desk. He lifts items up and then plunks them down with a thud.

When he asks me about my career goal, I say I want to be a writer.

He pauses for a moment and says as a blind person I would probably make a better psychologist, because blind people listen so well. I squeeze my hands together, bite my lip and try to quell the old warm feeling creeping up my body. I take a breath in an effort to compose myself, but the tears come anyway, dripping, cold and wet down my face.

These weren’t tears of embarrassment. They were tears of anger.

How could blind people succeed in a society that accepted and encouraged such stereotypical prejudices? How many times had I heard this kind of ignorance? I thought of the other stereotypes about blindness: black-clad people with dark glasses, a rocking head and faltering step, people who see nothing but black. I thought about our history, a history of basket weavers, beggars, the institutionalized, the helpless.

I thought about another history, the Helen Keller’s with exceptional super-human traits; people who conquered all obstacles. I realized how inaccurate and inadequate was our history.

Mr. Clark continued to talk, but I no longer listened.

On my graduation night, I walk across the stage to receive my diploma. The silky fabric of my dress rustles against my legs, the clunk of my high-healed shoes echoes in the vast auditorium. The sound of 3,000 people breathing electrifies the room. My cane vibrates in my hand as it runs along the stage, and I become aware of its solidity. The tap, tap, tap sound reminds me of my heritage.

I feel liberated in a way I’ve never felt before, and I know I must keep fighting.

MARCHING TOGETHER

This section will regularly feature a piece about how our members, as a group, take action against discrimination.

BIGOTRY ABOUT BLINDNESS

It’s So Deep-seated, Most People Don’t Know It’s There

Back in the fall of 2000, Victoria artist Jimmy Wright donated some of his paintings to raise money for the local elementary school strings program, which School Board trustees cut in a five-to-four vote. One of these paintings depicts the five trustees who voted to cut funding as blind people with white canes leading a procession of children.

In a telephone conversation, Oriano Belusic, President of the Canadian Federation of the Blind, and Dr. Paul Gabias, who is himself a school trustee in another district and blind, asked Wright why he had used blind people and white canes in the painting. Wright said the painting was a metaphor, reflecting lack of foresight. He said it expressed his feelings about the five school trustees who have no vision or sense of direction, just like blind people.

When Belusic and Gabias said they were blind and explained their objection to Wright’s portrayal of blindness, Wright said they were too sensitive and abruptly ended the conversation.

Members of our group wrote a news release about the situation. We sent the release to local media on September 16, 2000, a few hours before Wright’s painting went on sale at a fund-raiser.

Victoria News printed an article on September 22, 2000, weekend edition.

Journalist Jeanine Soodeen covered both sides of the issue, but made the federation seem petty for worrying about something that Wright called “ridiculous.”

The Times Colonist also printed an article in its September 21, 2000 edition. Writer Jim Gibson portrayed the Canadian Federation of the Blind as creating a “wall of political correctness” and interfering with an artist’s right to creative freedom. He lambasted our group for ridiculing Wright who, he said, was only trying to do something good for the community.

Below are samples of letters written by our members in response to this unfavourable media coverage.

Paul Gabias Ph.D., LL.D

Jim Gibson missed the point of the protest against Jimmy Wright’s painting issued by the Canadian Federation of the Blind. In his September 21 article: ‘Generous artist hits wall of political correctness’, Gibson wrote: “But Oriano and his group aren’t interested in symbolism or art. It’s irrelevant to them that blindness as a metaphor has an artistic history dating back to somewhere after the first scribblings on tablets.”

It is precisely that ancient metaphor that bothers us.

Wright’s painting reinforces ancient myths about blindness through an inappropriate, contextual use of the white cane. The white canes in the painting are meant to convey disparagement.

For us, as blind people, the white cane is a means of independence. It means pride and accomplishment. We will not allow it to be used as a symbol of disparagement. We have fought too long to change society’s perception of the white cane as a symbol of hopelessness and helplessness. We will fight against anyone who tampers with the true meaning of the white cane no matter what his or her good intentions.

In the eyes of the public, blindness and the white cane go together like motherhood and apple pie. It is precisely the metaphor of blindness associated with lack of “foresight, discernment, or moral or intellectual light”, that the Federation is against. We will not tolerate the white cane being used in this context.

We don’t want the ancient metaphor of blindness reinforced in any painting regardless of the reason.

Cary Faris

I am eight years old, and I am in grade four. My name is Cary, and I am writing to say how unfair that picture was to blind people. I have seen it myself, and it makes me feel sad, angry and upset all at the same time! I am mostly mad about how he showed the five blind people guiding kids, like they didn’t really know what they were doing.

It makes some blind people feel bad about themselves and unhappy because they are blind, and then they think they can’t do anything. The only thing that makes us different is our eyes. People who are blind are just as good as people who are sighted, and that picture teaches sighted people that blind people are just trash. This is wrong!

Greg and Karen Faris

As the parents of five children, we are aware of the merits of a musical education for children. We are also strong supporters of art and the freedom of artistic expression. We are, however, at a complete loss as to why Jimmy Wright felt he had to depict blind people in his painting in an effort to raise funds for School District 61’s strings program.

There is a definite line between the right to freedom of expression and the reinforcement of the prejudices of our society, and Wright unquestionably crossed that line.

Canada is proud of its multiculturalism, diversity, and ability to embrace all its population. Yet Wright’s actions are defended and justified as a means to an end.

What happens to the right of adults who are blind to feel equality with their fellow Canadians? What happens to the right of children who are blind to grow up with the same self-confidence and self-worth as their peers? And what happens to a society that embraces wholeheartedly the right of one individual to malign and degrade a minority segment of our population for the sake of a worthy cause?

As a citizen of this country who just happens to be sighted, I am shocked and disappointed to see blatant prejudice exhibited and condoned by our society. No one human being has the right to use a minority, metaphorically or otherwise, to further his/her cause. Jim Gibson attempts to justify this painting as “OK” because he interprets the figures in question as “tiny.” A seed of prejudice, no matter how “tiny,” is effective.

Elizabeth Lalonde

Jim Gibson argues that Jimmy Wright’s painting of five blind school trustees holding white canes has nothing to do with blind people. He says the picture relates instead to the other definition of blind that he quotes from the dictionary as “without foresight, discernment, or moral or intellectual light.”

I disagree.

I believe Wright was referring to blind people in his painting. He wanted to show the school trustees’ ignorance or metaphorical blindness, and the best way to do this, he felt, was to paint a picture of blind people. I agree with Gibson when he says that for centuries blindness has artistically been compared to ignorance.

Many like Gibson may argue this comparison has nothing to do with blind people themselves. However, as Wright has shown in his painting, it obviously does.

Because most blind people haven’t argued publicly against this negative perception of blindness, we are expected to continue saying nothing and accepting these ideas without complaint. When we stand up for our dignity, we are said to be “upstarts.” When we resent being associated with lack of foresight, we are said to be burdening the public with political correctness.

I understand the argument for creative freedom in art. But what disturbs me most about the picture isn’t the artist’s right to paint it, but that no one acknowledges the obvious connection Wright makes between blind people and ignorance.

I also agree that music is an important part of a child’s education. I am only disappointed that to defend such a worthy cause, he had to damage the image of blind people.

Frederick Driver

I was disturbed by Jim Gibson’s arrogant dismissal of the legitimate concerns raised by Oriano Belusic, president of the Canadian Federation of the Blind. I have seen Jimmy Wright’s painting; it deliberately uses blind people as a metaphor for the stupidity of the school trustees’ decision to cut the strings program.

Gibson says “blindness as a metaphor has an artistic history dating back to somewhere after the first scribblings on tablets.”

But the patriarchal oppression of women also has a long history. Anti-Semitism has a long history. Slavery had a long history. Would Gibson argue that their long histories legitimize them? I hope not, but given his disparagement of the blind, I would not be surprised if he thought metaphors insulting to women, to Jews or to blacks were acceptable.

Letter-writer Josephine Macintosh (Sept. 25) criticizes the federation for taking the painting literally. But they do not: they have recognized it as a metaphor, but it is precisely in this metaphor that prejudice lies. You cannot at once use a group of people as a metaphor for something negative and claim not to be maligning them.

Wright is a talented artist, and clearly generous with his money. But this does not justify his maligning and stereotyping blind people. I applaud Belusic for challenging such bigotry.

Dr. Gabias Receives Honourary Degree

BY ORIANO BELUSIC AND RICK DRIVER

In 1999, members of the Canadian Federation of the Blind nominated Dr. Paul Gabias for an Honorary Doctorate award. The University of Victoria Millennium Honorary degrees recognized outstanding individuals whose contributions reach into and have implications for society in the twenty-first century. Dr. Gabias, a member of the Canadian Federation of the Blind, was one of a select group of recipients that included luminaries as Louise Arbour, Maude Barlow, Helen Caldicott and Her Excellency the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson, Governor General of Canada. This achievement sent a positive message to the public about the abilities of blind people.

The week-long Millennium Festival celebrated achievements and included concerts, art exhibits and social events. Dr. Gabias and his guests attended a formal banquet at Government House hosted by the Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia. The week’s festivities closed with a luncheon hosted by the Canadian Federation of the Blind, which was attended by thirty Federationists, family and friends from as far away as Quebec and Ohio.

Dr. Paul Gabias was born and raised in Montreal and is fluent in English and French. He graduated cum laude from Concordia University and received his Ph.D. in experimental psychology from New York University in 1988.

He worked in Wisconsin, Nevada, Colorado and New Brunswick and is now a professor at Okanagan University College in Kelowna, where he lives with his wife Mary Ellen and their four children.

He served as President of the National Association of Guide Dog Users, a division of the National Federation of the Blind in the U.S., and successfully trained six dog guides. Paul is passionately committed to the blind movement in Canada. He faces discrimination with strength and resilience, as he has been evicted from a theatre and threatened with eviction from his home because he had a guide dog. With the support of his friends and colleagues of the National Federation of the Blind, he won the case and continues to fight tirelessly for the equality and civil rights of people who are blind.

In the words of Dr. Marc Maurer, President of the NFB, “Dr. Gabias is one of the most aggressive advocates for the rights and interests of blind people, and an authority in the research of tactile understanding.” Paul knows first-hand the empowerment of collective action.

He attended his first convention in New York in 1973 and was deeply impressed by the NFB’s positive attitude toward blindness. He shared this liberating philosophy with other Canadians. He introduced hundreds of Canadians to Federationism and helped lead the organized blind movement in Canada.

Through The Eyes of Pity

BY MARY ELLEN GABIAS

It was one of those days that lives in a mother’s heart forever. The late August sun felt warm on my shoulders, and a soft breeze ruffled my hair. But it was my six-year-old son Jeffery, not the weather that made the day memorable.

I am the mother of four. With all the activities in our home, it is difficult to arrange time alone with one child. It was particularly hard a few summers ago, when our family spent six weeks traveling by train across the United States.

Our odyssey began with a four-day-train journey from our home to Atlanta, the site of the 1999 National Federation of the Blind Convention. My husband Paul is a college professor. We are both blind. We get information and encouragement from attending NFB conventions. Our sighted children learn that our positive belief in blind people is right.

The convention is stimulating, but exhausting.

We boarded our train after a week in Atlanta and had no trouble sleeping on the journey north to upstate New York, where we spent some time visiting with Paul’s family and attending his niece’s wedding. Finally, we went to Ohio and visited with my family.

It was a good trip, but after eight days and nights on 10 different trains, staying in three private homes, a rented cottage and two hotel rooms, it was a relief to return home.

Paul resumed his duties at the college, but our children still had four weeks of vacation left, four weeks to get on one in other’s nerves. One day about a week before school started, it became clear the kids needed some time away from each other.

“Mom, she’s looking at me with a funny face.”

“Mom, he touched my stuff.”

By the end of the day, I bellowed, “if motherhood were a paying job I’d quit.”

A good night’s sleep brought the return of perspective and a plan for preventing a repeat performance. My daughter spent the day with friends. Paul cuddled with the two youngest on the porch swing. Jeffery and I went to do errands.

As my son and I waited for busses and walked from one place to the next, we talked. Jeffery tried to teach me all about “Pokemon,” but I failed his course dismally. We talked about violence and fighting and the difference between right and wrong.

“Mom, God is the boss of the universe, so why doesn’t he make all the bad people good?”

We discussed the environment.

“Mom, I know how we can get rid of the flies that come into our house without swatting them. Spiders eat flies. We could just get a bunch of spiders, and they would catch all the flies. That would make Joanne’s friends scream.”

Before we knew it, the errands were finished, and we were both hungry. We took the bus to the mall and wound our way through the labyrinth of corridors to the food court. Jeffery was nervous, afraid we’d get lost. But I reassured him as I led the way. He stopped once in a while to read the letters on signs.

“What’s ‘b l g s a l e’?”

“That’s not ‘b l g’, Jeffery. It’s ‘b i g’, big. The capital ‘I’ looks a lot like a small ‘i’. In first grade you’ll learn how to read. It won’t be long before you figure out those signs by yourself.”

I stopped to buy Jeffery some chicken strips and went to another place for my salad and fish. Occasionally we asked customers to help us with directions. They were always willing to assist, and everything went smoothly.

Jeffery searched for a table while I waited for my food. I thought about how grateful I was for such a perfect afternoon. In that moment, I knew I wouldn’t trade places with anyone. The proprietor at the food stand handed me my tray, and I turned to walk to our table. Behind me I heard the voice of another customer speaking to the man who had just waited on me.

“Look at that poor blind woman. Seeing someone like her makes you realize how lucky you are to have your sight.”

I was stunned. There I was, going about my business with competence and joy, and this man saw me as an object of pity. Worse, he felt no hesitation in speaking his mind in front of my child. Didn’t he realize his comments could undermine Jeffrey’s attitude towards me? If this man were an employer, no blind person would receive a fair chance at a job in his place of business. The more I thought about what the man had said, the more my mood changed. My exhilaration turned to exasperation.

Then I thought again. Fortunately, Jeffery hadn’t heard what was said, but even if he had, there was no chance the offhand remark of a stranger would carry more weight with my son than the years I spent breast feeding him, kissing his bruises and scrapes, and nagging him to clean his room. Yes, negative public attitudes about blindness do terrible harm, but positive blind people working through the Canadian Federation of the Blind and the National Federation of the Blind in the U.S. are counteracting those negative attitudes.

That man was looking at me through the eyes of pity, but more and more people are taking a new look at blindness and respecting what they see.

It was easy for me to realize what that man’s attitudes cost me, but I started to think with sadness what those attitudes cost him.

Because he was looking through the eyes of pity, he saw what he thought were problems, but didn’t notice I had found solutions. Because he was looking through the eyes of pity, he couldn’t approach me as an equal, and he lost the chance for the give and take of equals. Most of all, because he was looking through the eyes of pity, he missed the simple pleasure of watching a mother and child enjoying each other’s company.

Yes, that man lost a lot because he looked at me through the eyes of pity. None of us can choose how well our eyes see, but we can choose how well we see the world.

Do you have a computer you’re not using anymore?

If so, the Canadian Federation of the Blind recycles computers and makes them available, for free, to blind people.

If you would like to donate your computer, please call us toll free at 1-800-619-8789 or email us at info@cfb.ca

Back to Blind

BY ELIZABETH LALONDE

As a little girl, I called myself visually impaired. My tongue twisted around the awkward words, and people’s minds twisted around their meaning. The words signalled vision of some sort, but how much, how clear? Could I see colour, detail, classmates’ fingers held in front of my face? Maybe I could see more than that. Maybe all I needed was a pair of glasses.

When I tired of “visually impaired”, I tried the old standby: “I can’t see very well,” my little girl’s voice, shy and high-pitched as I looked sideways at my teacher. Well, the words “I can’t see very well” earned me a desk in the front row and the chance to stand close to the teacher while she wrote times tables on the chalkboard. But that’s all they earned me.

These days there is a trend to use terms that reflect the degree of sight a person has. Phrases such as visually impaired, sight impaired, partially sighted, visually challenged, visual disability and so on cloud our lexicon of blindness language. People choose from this hodgepodge of words and phrases to avoid the term we in the Canadian Federation of the Blind are proud to use: “blind”.

Substitutions for the word “blind” are common in the blindness community. Organizations publish Canadian blindness literature with titles that contain words like vision and sight. Organizations and support groups for blind people also commonly have visual names.

Aside from the lack of clarity, another, larger issue emerges from the hesitance to use the word blind. The avoidance of “blind” implies a sense of shame and discomfort associated with blindness.

The insistence on using terms that depict some degree of sightedness demonstrates people’s beliefs that to have some sight, no matter how little, is better than having no sight at all.

I like the word blind because it is accurate. It specifies something, rather than a lack of something.

As I grew older and more comfortable with myself, I sensed the wisdom in using the word blind. At first, I called myself blind to help people understand how limited my vision was. I preferred people to think I had less rather than more sight. At least there would be fewer misunderstandings, fewer hand gestures and no questions about why I didn’t wear glasses – like carrying a white cane, calling myself blind made my life easier. But these adjustments were only surface changes.

The real transformation came when I took pride in the word blind, when its negative connotations left and positive ones grew, when I saw myself as part of a group of strong, proud people who were not ashamed to be blind.

Once a taxi driver asked me how long I had been “that way”. He was obviously afraid or ashamed of the word blind. So I turned to him and said, “you mean how long have I been blind?”

Members of the Canadian Federation of the Blind are not ashamed of the word blind and are not ashamed of being blind. We believe the amount of vision one has in no way relates to one’s competence or ability. The only things that make a difference, no matter what degree of blindness one has, are training, opportunity and attitude. With proper training, sufficient opportunity and a positive attitude, blind people, with or without residual vision, can achieve success.

Braille = Literacy

BRAILLE LEARNING GROUP IN VICTORIA

It’s fun! And free!

For information, or to join, call:

598-7154

FUNDRAISING

Succulent steak. Lobster. Fresh vegetables. Fine cheeses… Would you believe you can contribute to the Canadian Federation of the Blind simply by eating? The Thrifty Foods Gift Certificate Discount Program is as easy as pie, and a great way to donate to the Federation at no cost to you. Here’s how it works.

Thrifty Dollars are available in denominations ranging from $5.00 to $50.00. In exchange for the cash value of your choice, we give you the equivalent value in Thrifty Dollars. Then you simply use these Thrifty Dollars instead of cash when you go shopping at Thrifty’s. For example, if you give us $25.00, we will give you 25 Thrifty Dollars, which you can use to buy $25.00 worth of groceries at Thrifty’s. A portion of what you spend automatically goes to the Canadian Federation of the Blind. And it costs you nothing! What could be easier?

Everyone eats, so the Thrifty Dollar Program means steady revenue for the Federation.

We also do occasional fundraising like bottle drives and garage sales. So if you have items to donate, or would like to join the Thrifty Dollars Program, give us a call.

Funding permitting, The Canadian Federation of the Blind provides long, white canes to blind people free of charge.

For more information about this service, please call us toll free at 1-800 619-8789 or email us at info@cfb.ca

The Education System for Blind Students in British Columbia: Is More Better?

BY KAREN FARIS

Summary of the Canadian Federation of the Blind’s Thoughts on Educating Blind Children.

We, in the Canadian Federation of the Blind, do not necessarily advocate increased funding for blind students in the education system. We live in a society that assumes more is better, a society that labels children even if they just have small differences, a society that thinks differences are deficits.

People unquestioningly assume that if a child has a disability, the system must call upon highly sophisticated programs with specially trained professionals. Sighted people, who view the world primarily through vision, might find it hard to comprehend that a blind child can function without sight. But this attitude ignores the inherent adaptability of human beings.

A baby born without vision will automatically internalize stimuli from the environment with his or her other four senses, just as a baby born without hearing will adapt to a world without sound. We must recognize the normalcy of disabilities and the adaptability of children. We must strive to enhance the gifts and tools already available to all children including blind children.

Intervention in the development of blind children starts in infancy, continues through Child Development Centre programs and into formal education, with far-reaching results. As the normal blind child progresses through this system of intervention, parents gain the impression their child is not normal.

By the time he or she enters the school system, the de-normalization is firmly entrenched. No one, not even the child, views blindness as normal. Her self-confidence and emerging identity, her natural curiosity and adaptability, suffer serious damage in the process.

A few years ago, the Canadian Federation of the Blind submitted a brief to the Ministry of Education promoting changes in the approach to the education of blind students. We do not advocate an increase in blindness professionals, nor do we necessarily recommend an increased budget for services for blind students. We emphasize the importance of learning Braille and travel skills, together with the intellectual and social components of a curriculum. These skills must be achieved hand-in-hand with the self-confidence that comes from realizing one’s potential.

We must remove the mystery from blindness. Parents, staff and students must realize that a common sense approach to blindness can accomplish far more than a complex service delivery system that overestimates the deficits and underestimates the potential of blind children. We must change what it means to be blind, encourage normal growth and development and remove the intervention approach to learning. We must promote programs that facilitate input from competent blind adults and create a supportive, can-do environment for blind children.

Blind children are normal children and blind adults are normal adults. Let us celebrate their strengths and abilities as well as their differences in the positive spirit of diversity.

The Canadian Federation of the Blind welcomes donations and bequests.

They are greatly appreciated and helpful to our cause. But ultimately, we are not asking for your money.

We are asking you to open your mind to a new and positive concept of blindness.

Canadian Federation of the Blind

1614 Denman Street

Victoria BC (Canada) V8R 1Y1

Tel.: (250) 598-7154

Toll free: 1-800 619-8789

E-mail: info@cfb.ca

Web site: http://www.cfb.ca

The Blind Canadian is published by the Canadian Federation of the Blind in Braille, on cassette tape, by e-mail, on disk, in large or regular print, and on our Web site. It is free of charge, but donations to cover production costs are appreciated.